A few days ago, Christopher Howse wrote an article in the Daily Telegraph about my hometown, Sunderland, and told a tale of closed, boarded up shops up left to decay and of general poverty. It was, of course, journalistic exaggeration. There are some very nice areas of Sunderland, and it still has much going for it, not least fantastic beaches and beautiful surrounding countryside. However, there is also a lot of truth in what Howse says and, in my view, it goes a long way to explain the explosion of anger that resulted in working class areas recently erupting in protest, some of which led to violence.

I have found that many good, well-intentioned middle-class people, especially in the Southeast, simply do not understand the causes behind that anger and so fall all too easily into the false narrative of racism the Establishment is pushing out so enthusiastically. So, I thought I would try to explain, and use Sunderland, which experienced some violence during the recent anti-immigration protests, and which voted heavily for Brexit, as an example.

But first something about the town, as I expect that few have been or know much about it. Sorry it’s a bit long, but I think it important to understand what has been lost over the last thirty to forty years.

Sunderland is located at the mouth of the River Wear and that has shaped its history. The Venerable Bede (672-735), one of the early Middle Ages’ most influential figures and the author of the Ecclesiastical History of the English People was a Sunderland lad.

Bede possibly invented and certainly popularised dating forward from the birth of Christ, Anno Domini and is considered by many historians to be the most important scholar of antiquity for the period between 604 and 800. The Codex Amiatinus, described as the 'finest book in the world' was created at Bede’s monastery, St Peter’s, and was likely worked on by him. He also wrote that he was “ácenned on sundorlande þæs ylcan mynstres" (born on the land sundered from this monastery).

Bede toiled on his beautiful manuscripts at St. Peter’s, on the north side of the Wear half a mile a mile from the sea, in the area still known as Monkwearmouth. The church, built in 674 AD by another hugely influential figure of that era, Benedict Biscop, is still there. Biscop might also have been born in Sunderland. He certainly died there. St Peter’s is thought to be the first building in the British Isles to have had glass windows, made in the town by glaziers Biscop brought from France. Glass was still being made, by Pyrex, in Sunderland over 1,300 years later.

A mile upriver, on the other side in the modern town centre, is Bishopwearmouth, given to the Bishop of Durham in 970 by King Æthelstan. County Durham, the Land of the Prince Bishops, was a palatinate, tasked by the King to govern the unruly North.

In 674, King Ecgfrith of Northumbria granted Benedict Biscop the land opposite Monkwearmouth, on the south side of the river. This small fishing village called in the grant the ‘sundered land’, cut apart from the important monastery by the river.

Little is known of what happened for the next few hundred years. The Vikings raided and established overlordship, but didn’t settle and the area remained part of the Northumbrian Kingdom of Berenicia and of Angle stock. The Normans came, and built a castle at Hylton, four or five miles from the mouth of the river where it could be crossed on foot as a centre for the Harrowing of the North. In the winter of 1069 - 1070 the Norman William faced rebellion in the North and set about systematically destroying large parts of it. According to a chronicler “he made no effort to restrain his fury and punished the innocent with the guilty. In his anger he commanded that all crops, herds and food of any kind be brought together and burned to ashes so that the whole region north of the Humber be deprived of any source of sustenance”.

A charter was granted to 'Soender-land' in 1179 giving its merchants the same rights as those of that Newcastle-upon-Tyne (who spent the next five hundred years trying to revoke it). By 1346 ships were being built at Wearmouth and by 1396 coal was being exported to London. Shipbuilding and coal mining would be the mainstay of Sunderland’s economy for almost all of the next six hundred years.

In the English civil war Sunderland declared for parliament, Newcastle for the King. The two towns had long been rivals, but now they were at war, and even fought a battle against each other! Parliament blockaded the Tyne shutting down the coal trade. Sunderland boomed. Newcastle tried to take revenge after the Restoration.

Over the next couple of hundred years Sunderland’s industry grew, based on the coal industry and cheap coal. The river was lined with shipbuilding yards and the town was Britain’s fourth biggest port in terms of tonnage. A modern glass works was established, and the world’s first steam dredger was built (driven by a Boulton & Watt engine). A pottery was established, as was the world’s first mechanised ropery. The world’s second iron bridge was built across the Wear.

George Stephenson built the world’s first, and briefly longest, railway operated entirely without animal power in 1822 to carry coal to the port, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed a dock. In 1835 the then world’s deepest coal mine was opened where Sunderland football stadium now stands. By 1850 a third of all the ships built in the UK were built in Sunderland, including some of the fastest clipper ships. As sail gave way to steam, marine engine works, and then electrical machinery works were opened.

In WW1, Sunderland men volunteered in disproportionately large numbers, and the town was hit by Zeppelin raids. Many of the men who had served and survived spent much of the 1930s unemployed, when shipbuilding came to an almost standstill and demand for coal declined. Unemployment in the town exceeded 36%. My paternal grandfather, a shipyard riveter, was unemployed for almost ten years. My maternal grandfather, a coal miner and trade union activist, was jailed for six months, ostensibly for ‘stealing’ wood in the form of a damaged pit prop. Both had served on the western front in the Durham Light Infantry. The 1930s left a latent mistrust of the ruling class and are still not forgotten.

Nevertheless, in 1939 Sunderland rallied to the call to arms. In WW2 Sunderland built around 40% of all the merchant ships built in the UK and produced the design for ‘the ship that won the war’, the Liberty ship, built faster and better than the US yards usually given the credit.

Sunderland was heavily bombed, suffering more than any other town north of Hull and was the seventh most bombed town in Britain. Over 4,000 homes were destroyed, including my then 18-year-old father’s, who despite being in a protected job, a shipbuilding apprentice, immediately volunteered for air crew and flew as a gunner in Lancaster bombers. To this day, Sunderland holds the UK’s second largest Remembrance Day parade, after the one at the Cenotaph in London.

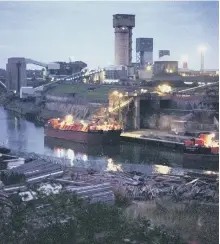

When I left Sunderland to go to sea in 1970 there were five major shipbuilding yards in the town, and Sunderland claimed to be the biggest shipbuilding town in the world. There was a world-famous ship’s engine builder, and the maker of much of the electrical equipment that went into the ships.

The coal industry, with many coal mines within and around the town, supplied much of London’s coal. Wearmouth was the most productive deep mine in the world and Pyrex produced vast volumes of glassware. Other firms built cranes, and Rolls Royce had a factory there. There was a major brewery in the town and the beginnings of a light electronics industry. All of these provided an abundance of reasonably well paid, skilled jobs. Lads leaving school at 16 could usually find an apprenticeship, even me, chucked out of school at 16 a couple of months before the end of term with no qualifications at all.

The town centre was busy, filled with shops and stores like Woolworths, where my mother worked before going to work in an electronics factory. On weekends the pubs and workmen’s clubs were heaving. The town centre could get a bit rowdy on Friday and Saturday nights with hordes of lads piling out of the pubs at half-past ten and showing off to the fleets of lasses, scantily clad even in January. Sunderland had pride, a history to be proud of and most thought that times could only get better. They did. Sunderland won the FA Cup in 1973.

Most were proud to be from Sunderland, proud to be English and proud to be British. And they were also proud of their history and proud to be working class. They were people who knew who they were, and who valued their identity. There was a rough and ready camaraderie about the place and a complete sense of shared values and togetherness.

But when I go back now, I barely recognise the place. It’s almost all gone. All the shipyards have gone. The mines have gone, and so have the engine works, the glassworks, everything. Even the brewery has gone. All that remains is the crane factory, now owned by an Austrian company.

Sunderland has a feeling of being abandoned. The town centre is a shadow of its former self. Almost deserted at night and not much better during the day. This isn’t the place to discuss what went wrong, but globalism and membership of the EU are certainly up there as primary causes, as is government neglect.

There are a few bright spots, such as the Nissan car factory, but in general there are few well-paid jobs and fewer prospects for the young. The fairly plentifully available apprenticeships for 16 year olds leaving school are no more, and all the reasonably well paid jobs skilled held by men like my father, a plater in the shipyard that designed the Liberty Ship, JL Thompsons, have vanished.

Few expect things to get better and most think that the government in London, Labour or Tory, cares little and does nothing except push ‘refugees’ their way – despite the fact that, in 2023 almost 25 per cent of those aged 16-64 were “economically inactive” and not seeking employment. Many feel that refugees get preferential treatment in health care, housing, education and even jobs. Naturally enough, this causes real resentment.

The ludicrously incompetent council declared Sunderland a ‘city of refuge’ and invited ‘refugees’ to come and settle. No, they didn’t bother to ask the people of Sunderland. A frequently made comparison is that between the favoured status of the immigrants and what is perceived as the hostility to our own ex-servicemen.

So far as I can see the Council fully supports the totalitarian globalist agenda and enthusiastically spreads its propaganda while attacking opponents as ‘far right’ and trying to shut them up. Until recently at least, it donated tens of thousands of pounds to groups like Antifa and the misleadingly named ‘Hope Not Hate’. Freeborn John Lilburne, another Sunderland lad, will be rotating rapidly in his grave.

A descendent of a Wearside family, the Washingtons, from the Sunderland suburb of Washington, fomented and won a revolution caused by taxation without representation. Sunderland has a very high council tax and many of its inhabitants feel disenfranchised.

Sunderland’s left wing council is widely regarded as being incompetent and worse. It does little for the town except make woke gestures, and is thought as having turned down applications for factories from industries it considers ‘unclean’, and is forever rabbiting on about ‘green jobs. Few of which have materialised, so I’m told.

This goes back many years. The council demolished a beautiful Victorian Gothic Town Hall in 1970 and replaced it, on a fine old park, with an ugly brick and glass block that had to be demolished in 2022. The people of Sunderland were told that the old town hall would be replaced by a new hotel, but it never happened, and the land stood empty for many years.

There are too many council failures to list here, but they sail on, uncaring, typical of what amounts to a one-party state. But one incident is worth telling, that of the Council selling an astonishing 36,356 council homes in 2001 for £219.8 million to a private housing association – a mere £6,045 each. Yes, I’m thinking exactly the same as you.

So, if tin-eared Kneel Two-Tier Keir Starmer wants to know why Britain’s worst riots in more than a decade happened recently, he should get on his bike and go to Sunderland and talk to the people there. He won’t of course, the man could only bear to stay at a memorial for the three murdered girls in Southport for three minutes, just long enough to get his photo taken and get back to persecuting ‘right wing thugs’, by which he means people like the white working class in places like Sunderland.

They would tell him that it is the feeling of abandonment, of not having hope, of significant deprivation – all made worse by constantly being nagged about ‘white privilege’ by smug middle class champagne socialists, not racism, that made them protest. They are angry, and have been for some time, and if the Establishment pays them no heed, they are likely to vent their anger in protests again.

Everybody I have spoken to rightly condemns the violence that took place. But there agreement ends. Some think legitimate protests were taken over by yobbos looking for a fight with police. Others agree but think that the police were just as bad, out for a fight. Others say that the violence has been much overblown. None thought there was any involvement by the mythical ‘far right’ of the Left’s imagination, as it simply does not exist in the town.

And the people are still angry, made if anything even angrier by the constant suggestion that anyone who opposes mass immigration and multiculturalism is a dangerous extremist, who must be shut up and prevented from expressing their opinions, even jailed.