This is the story of a good man. A German. Let’s call him Tommi Armstark, and this is the tale of the dilemma he and many other decent, law-abiding Germans like him faced in 1934, the year after the far left Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP/Nazi) came to power.

Tommi is fictitious, though there must have been many like him. The events portrayed here are real and happened to men and women most remarkably like me and you.

Tommi was 44 in 1934. Born into a working-class family in Hamburg, his Papa was a skilled steel erector at the shipbuilding yard of Blohm & Voss, where he had worked since it was founded in 1877. Mama stayed at home and looked after the family.

Tommi was 24 in 1914, when the Kaiser’s war began and with his two brothers joined the 76th (2nd Hanseatic)(Hamburg) Infantry Regiment of the Imperial German Army, serving as frontkämpfer on the Western Front. Tommi was the only one to survive. Mama died of grief at Christmas, 1918, leaving his father a bitter, almost silent man.

The year immediately following the end of the fighting in 1918 was very hard. The continued blockade of German ports by the Royal Navy caused widespread malnourishment. Employment was hard to find. Tommi had followed his father into the steel trade at Blohm & Voss, but work was patchy, on a day-by-day basis.

Tommi married Frida in 1920, and they had somehow managed to survive and produce a daughter, Herta, in 1921 and a son, Ernst, the next year.

Tommi was a patriotic man, and believed in the German values of hard work, family, church and love of the Vaterland. His experience of war had made him distrustful of politicians, all politicians. He voted Zentrum (Deutsche Zentrumspartei), which he considered a patriotic conservative party, but had slowly come to feel betrayed by them, all through Weimar. By the time they supported the Enabling Act in 1933, which effectively created a dictatorship, ending the already restricted right to free speech, assemble and protest (depending on whether or not you had approved views) Tommi hated them.

He had hated the unrest after the Armistice was signed by the November Criminals, the declarations of Soviet republics by Rosa Luxemburg and her Spartacists, as well as the Freikorp putsch of 1920, and was pleased when the Freikorp had to be disbanded. He was appalled when the Communists had taken over Saxony, Thuringia and the Rhineland in 1923.

He had been concerned about the de facto restrictions on free speech in 1922, following the Weimar government’s ‘Law for the Protection of the Republic’, outlawing groups that ‘promote, endorse or engage in acts of political violence’. In the eyes of the State, anything they didn’t like was classed as endorsing acts of violence, and there were police spies everywhere.

Tommi had, with increasing reluctance, stayed loyal to Zentrum and Weimar through the terrifying hyperinflation of 1923. In 1918, a loaf of bread had cost one quarter of a Reichsmark. In January 1923 it cost 700 Reichsmarks. By May it was 1,200, in July it reached 100,000. It was two 2 million by September, 670 million by October, and then 80 billion Reichsmarks in November.

Society was almost destroyed. Tommi was paid twice a day, and Frida would come to the shipyard, collect his pay and rush to the shops to buy as much as possible before their money became worthless. Savings were wiped out. Millions were impoverished. Many starved. The trauma was deep, and lasting. Ten years later Tommi and Frida still had nightmares about it.

At first Tommi believed the politicians when they blamed the French, who had occupied the Rhur in January 1923. Tommi was highly indignant about the occupation, but later realised that the hyperinflation was the result of the German government printing money to pay for the war, and to pay the striking Ruhr workers, a general strike it had encouraged.

Tommy had joined with some of his alte kammeraden to overturn the Communist takeover of Hamburg in October 1923. He had supported Hjalmar Schacht and the creation of the temporary new currency, the Rentenmark, backed by industrial property and pegged to gold and massive loans from the Amerikaner.

He had hoped that Zentrum would fulfil its promises in November when its Wilhelm Marx became the eighth Weimar chancellor in just five years. Tommi gave Marx credit for stabilising the currency, but was uneasy about his legal reform, which replaced the system of trial by jury with a system of trial by judges. His unease increased when it became apparent that this had political motives and was being used to suppress political dissent. Marx's introduction of family allowances for state employees only caused great animosity and further division.

Things improved for Tommi and Frida in 1924, and remained so up to about 1930. Politics was a mess, and there were no good options. The Weimar government was authoritarian and perceived to be anti-German. Two small but fast-growing parties, the Commis and the Nazis, offered alternatives, but both were extremist far left parties, prone to violence, squabbling about what form of socialism should be adopted, the internation socialism of the Commies and the German national socialism of the Nazis. Most Germans found them both abhorrent.

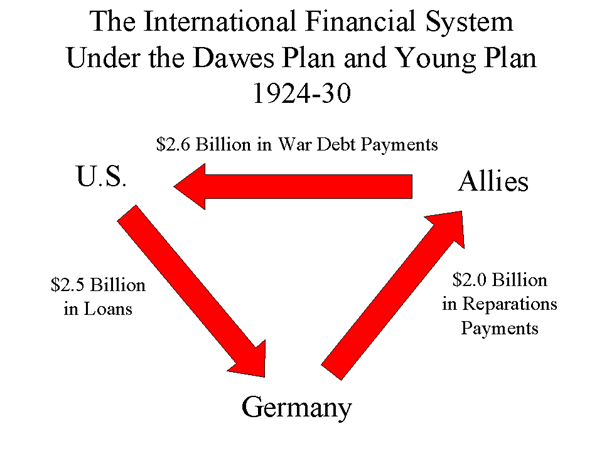

But few cared, really, and so long as the economy was doing alright, most kept their heads down and tried to make the best of things. Few understood that the economy was now highly dependent on American loans, used to promote US business in Germany, under the Dawes Plan. That had reduced reparations, but the money went straight back to the US: they were used to pay reparations to France and England, who used the money to repay war loans to the US – the only winner of WW1, which had done little fighting but made all the profits.

Tommi and many others had felt betrayed by the Locarno Pact the Weimar government signed in 1925. It was sold to the German people as a major concession to Germany, but in reality it consolidated the hated Versailles sell out, leaving the Rhineland permanently semi-detached from the Reich and the loss of the eastern Länder set in stone. The only beneficiary was the Establishment, now free to join the international elite. Stresemann was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Opponents had forced a referendum to oppose the plan, but it failed because of a low turnout, the general opinion being that the Establishment would implement it anyhow, so why bother.

And then came Black Tuesday, at the end of October 1929. The Wall Street crash, caused by the American government’s loose monetary policy, supply outstripping demand and the easy loans that had led millions of Americans to borrow money to buy shares.

The American loans to Germany were re-called and the economy, highly reliant on trade and exports, crashed. By May 1930 over four million Germans were unemployed. By the end of 1932 unemployment exceeded six million. Tommi was one of them. World trade had collapsed, and nobody was buying new ships.

Tommi and Freda’s plight, and that of the German working class became extreme. Wages fell, and unemployment benefits were strictly means tested. Tommi and Frida had to sell everything that was not essential for daily life, including Frida’s wedding ring. Most of those in work suffered serious pay cuts.

The atmosphere on the streets was febrile, with rival gangs of extremists battling it out, the police usually siding with the Nazis. Tommi’s daughter, Herta, now twelve, a clever but wilful girl, had joined the Jungmädelbund section of the Bund Deutscher Madel – nicknamed The League of German Mattresses - and was a rabid Nazi. It was prudent not to discuss politics in front of her. And preventing her attending was probably dangerous. Worryingly, football mad Ernst was talking about joining a Nazi football club.

In the March-April presidential elections, Tommi had, with great reluctance, voted for the authoritarian Hindenburg, who won, but who had been ruling by decree since 1930. He suspected that his wife Frida had voted, with equal reluctance, for his main opponent, Adolf Hitler.

The Reichstag fire incident in February, four weeks after Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor, was a major turning point. Tommi was convinced that the government was responsible and used it as an excuse for a violent crackdown on the Nazis opponents..

The street violence got worse. In July, just outside Hamburg, eighteen were killed in the Altonaer Blutsonntag, a mass brawl between the police, the Nazis and the Commis. Tommi knew five of those killed, two from Blohm & Voss and three from army days. Decent enough lads, four Commis, one Nazi.

I932 had been a year of general elections; two of them, one in July and one in November, with the Nazis coming out on top in both, but without a majority. They had won 230 seats in July, dropping to 196 in November. Tommi hadn’t voted in either, feeling disenfranchised. And then came the third election, the one in March 1933 that brought Hitler to power. There had been a nearly 89% turn out. Hitler got only 43% of the popular vote and Tommi was outraged that the Nazis gained power with only 38.4% of those eligible to vote.

Two weeks after the election, Dachau concentration camp opened and began receiving political prisoners. The next day, sick to his stomach, Tommi learned of The Enabling Act, allowing Hitler to pass laws without the Reichstag. Laws aimed at Jews became common. Tommi had served with Jews in the war, and had nothing against them, believing they had been made a scapegoat, but Frida had approved of the restrictions placed on them (though not of the later violence.)

It was hard to keep up with all the changes and Nazi action campaigns, such as the book-burnings, targeting “un-German” authors and the law for compulsory sterilisation for ‘the diseased’. This was soon followed by the Law for the Simplification of the Health System, allowing citizens to report candidates for sterilisation.

A new police force was formed to enforce Nazi thought and eliminate thought crimes, the Gestapo.

On August 2nd Hindenburg died and Hitler assumed his powers and became Fuhrer. A referendum a couple of weeks later asked “The office of the national president is united with that of the national chancellor. In consequence, the former powers of the national president pass to the leader and national chancellor, Adolf Hitler. Do you, German man, and you, German woman, approve of the arrangement made in this law?”

Tommi considered the result a fraud. According to the government, over 89% agreed in 96% turnout, but there was widespread intimidation and electoral fraud to secure the large "yes" vote. Storm troopers patrolled polling stations, forcibly escorting clubs and societies to polling stations. In some places, polling booths were removed, or banners reading "only traitors enter here" hung over the entrances to discourage secret voting. Many ballot papers were pre-marked with "yes" votes, spoiled ballot papers were frequently counted as having been "yes" votes and many "no" votes were recorded to have been in favour of Hitler. The extent of the fraud meant that in some areas, the number of votes recorded to have been cast was greater than the number of people able to vote.

Tommi concluded that Hitler’s government was illegitimate and was out to destroy Germany and the German people, with its insane Großraum Europa plans and the making of Das Neue Europa. But what to do about it?

To find an answer, Tommi discussed this question with his closest friend, Otto Meyer, who had been his feldwebel in the army and was Frida’s older brother. Otto shared Tommi’s views and they trusted each other absolutely. Increasing, they talked about how should a responsible, law abiding, conservative and patriotic German respond to dictatorial government that had destroyed free speech and personal liberty. At what point should the (little) legal opposition allowed be abandoned and civil disobedience used. And it that failed, was it permissible to resort to violence?

They, and occasionally thrusted others, all intelligent but not highly educated men, talked of the legitimacy of opposing Hitler through civil disobedience. They found it endlessly complex, trying to determine when civil disobedience might be considered legitimate. They took it is a given that their government was enacting laws and policies that violated fundamental human and constitutional rights, removing rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the right to a fair trial.

The normal democratic processes for change were unavailable, and meaningful change through legal channels impossible. The law itself was profoundly unjust and immoral. They rarely talked about the consequences of opposing the Nazi regime, but the question was there, lingering like a bad smell.

They considered civil disobedience to be generally more legitimate if nonviolent, and at first were in favour of bringing about change without causing harm, thereby maintaining a higher moral ground and public sympathy and support. They saw civil disobedience as a last resort after other methods had been exhausted.

On the other hand, the Hitler regime was undeniably popular with a significant proportion and most of the rest were apathetic. The level of public support went a long way, in their view, to legitimise civil disobedience. So regardless of the morality and rightness of their cause, did lack of support render action illegitimate?

Ultimately, the legitimacy of civil disobedience would be judged in hindsight, based on the outcomes achieved. It all came down to the individual, weighing the potential benefits against the risks and consequences.

But all the time things got worse. Not economically, Hitler’s socialist make work schemes brought unemployment down and people had a little more money to spare. Living standards were well below that in England, let alone in Amerika. But still, public housing was being built and the socialist ‘volks’ program was cranking up, aiming to get cheap Volkskühlschrank (people’s refrigerator) and Volkswagen (people’s car) and, especially Volksempfänger (people’s radio) for propaganda purposes to people.

But the free speech and personal liberty situation was becoming extreme. People were being jailed because their neighbours had reported them for anti-establishment rhetoric. Judges imposed savage sentences on dissidents, but relatively light ones on regular criminals. Because of this, the talk between Tommi and Otto began to change, with the possibility that the time for civil disobedience, or only civil disobedience, had passed. Whether or not violence could ever be justified began to be discussed. After all, the German government had demanded that they use violence in the Great War to further German interests. Was the situation now so very different. The State had power, but not right or legitimacy.

Could violence against the regime, they asked themselves, be considered comparable to a just war, perpetrated to protect innocent lives and defend human rights? Had they, the relatively small number prepared, perhaps, to act a legitimate authority? Had all non-violent options been exhausted – a question they took very seriously.

Is it the case that when a dictatorship systematically violates human rights, violent resistance may be morally justified to restore those rights? The law prohibited violence against the State, but as the State itself was illegitimate, even criminal, it may be reasonably be seen as lacking moral authority.

Another major factor in their thinking was the obvious fact that violent resistance against the Nazis could lead to more harm than good, was likely to fail and lead to further repression.

And so they dithered, but then Tommi learned that Hitler was to visit Hamburg on 17 August. Tommi had an army pistol and thought long and hard about shooting Hitler. He talked to Otto about it, but Otto said it would be wrong and could not be justified. In the end Tommi agreed and did nothing. Hitler received a hero’s welcome – all staged by the local Nazi party and Gauleiter Karl Kaufmann.

And that’s it. Nothing was done. All those good, decent Germans did nothing much to oppose the increasing mad National Socialist regime.

Life got worse, much worse. Tommi’s son Ernst joined the Hitler youth and then, in 1939 when he was 19, the Großdeutschland division of the Wehrmacht, and was killed in February 1943 in the Third Battle of Kharkov. The only notice Tommi and Frida got was one of their letters to Ernst returned to them, stamped gefallen für Großdeutschland.

Their daughter Herta had been assigned, or volunteered, to enter the Lebensborn project, as a racially pure woman, to have sex with SS officers in the hope of producing an Aryan child. By the end of the war she had given birth to two of them. She did not know who the fathers were. She was now, in 1945 having sex with British soldiers for money, chocolate, bars of soap.

Tommi and Frida had been bombed out of two homes by the British and Americans, and Frida was a mental wreck. Tommi feared for her, and often wondered whether he had made the wrong decision not to assassinate Hitler back in 1934.

So, what do you think? In 1930s Germany would it have been legitimate for German to have resorted to civil disobedience? Would Tommi have been justified in shooting Hitler?

There are two poll here. Click on the arrow to move between them.