I suppose people do still remember A. A. Gill? He died only eight years ago and was amongst the best known English journalists: “the shiniest star” in the Sunday Times’ sky said Lynn Barber; “the heart and soul of the paper” and “a giant among journalists” said the paper’s editor Martin Ivens; “Known for his sharp wit … was widely read and won numerous awards for his writing,” including “‘Hatchet Job of the Year’ for his scathing review of Morrisey’s Autobiography,” says Wikipedia.

He makes, then, a good touchstone of that ‘quality journalism’ that calls itself so and which is sometimes called by outsiders the msm. One of his specialities was travel writing, and in 2002, on returning from Japan where he had been sent to report on the Japanese, he published his report in the Sunday Times Magazine as “Mad in Japan”.

Gill was plainly not a fool. He was clever and he was educated, but not pretentious or academically hi-falutin’. He was too well educated for that. (It perhaps helped that he didn’t go to university.) He had a robust common-sense, which wasn’t easily taken in and which had perfect confidence in itself. His style was fluent and varied, moving easily between the demotic and the high-brow. It is a style a great many professional journalists aim at but few so successfully.

“Mad in Japan” was a very polished piece of modern ‘quality’ journalism. It flattered its readers that they were reading something intelligent and authoritative while making no demands on them. It was calculated to go down smoothly and trouble no one’s digestion. It was, I would say, perfectly cynical. It must have pleased the editor who commissioned it as giving him exactly what he wanted. If there were the demand (i.e., payment), Gill, as a good professional, was well equipped to supply something similar about any country at all, including his own. It was just a matter of retaining the formula such pieces are written to and using different examples. The examples might very easily be, and sometimes were, English, the Isle of Man, Norfolk, Grimsby, Cleethorpes — those sorts of places.

It was a measure of the writer’s intelligence that he could advise the Westerner trying to make sense of Japan to “stop reading the signs as cultural and read them as symptoms”. It was a measure of his cynicism, and perhaps of a deep stupidity, that he betrayed no consciousness that the article in which he said so might itself be read so.

How high-mindedly he looked down on those Japanese! They felt no remorse for the terrible crimes they had committed during the war. They were so superficial that what they made even of their own suffering in Hiroshima shocked him by its lack of gravity. They lacked love — brotherly, charitable or sensual (their women were either silent household drudges or sex toys). And they were wanting religiously. Their religion — such as it was — lacked even a rudimentary theology. It was without solace, salvation, redemption, hope or encouragement.

The place, then, to go for these things must surely have been A. A. Gill himself. (How else should he have the neck to scorn their absence in anyone else?) What else could have inspired him, a reader might ask, but brotherly love, gravity, remorse, hope, solace, redemption? What, for instance, by contrast with the Japanese’s own superficiality, did he make of Hiroshima?

Well, any sympathy he might have had was snuffed out by the petition they asked him to sign wanting the Americans to apologise for it. If you asked him — with the benefit of hindsight — Hiroshima was a very good thing, the best thing — all things considered — that ever happened to them. It may have killed 140,000 men, women and children, including 20,000 Koreans, but it was the starting gun for the modern Japan he despised. It created far more than it ever destroyed. It created what was then the second biggest economy in the world, with a GDP as large as Britain’s, France’s and Germany’s combined.

So, if we read A. A. Gill as he says we should read the Japanese, as symptoms, what would our diagnosis be? Brotherly love, remorse, hope, solace? Or the cynicism of a hypocritical old hack who’s a credit to his profession?

And why did Gill and his editor single out the Japanese? Rather than the Uzbekistanis or the Peruvians, say? After all they had the whole world to choose from. And the Japanese aren’t terrorists. They don’t practise female genital mutilation. They don’t go in for forced marriages. Thousands of Japanese wives aren’t murdered by their in-laws every year. Their boys don’t grow up “in the absence of male role models”. They don’t routinely kill girl babies or torture and murder children for practising witchcraft. Weird, they may — or may not — be but the weirdest, by a long chalk, they ain’t. So why them?

It is, I am afraid, because we’re a bit weird ourselves. For us, they fit the bill. And fit it pretty well uniquely. Modern English journalism has a difficult balancing act to perform. To sell papers and get attention, it has to shock, but it has to do so without giving offence to politically important groups called “communities”.

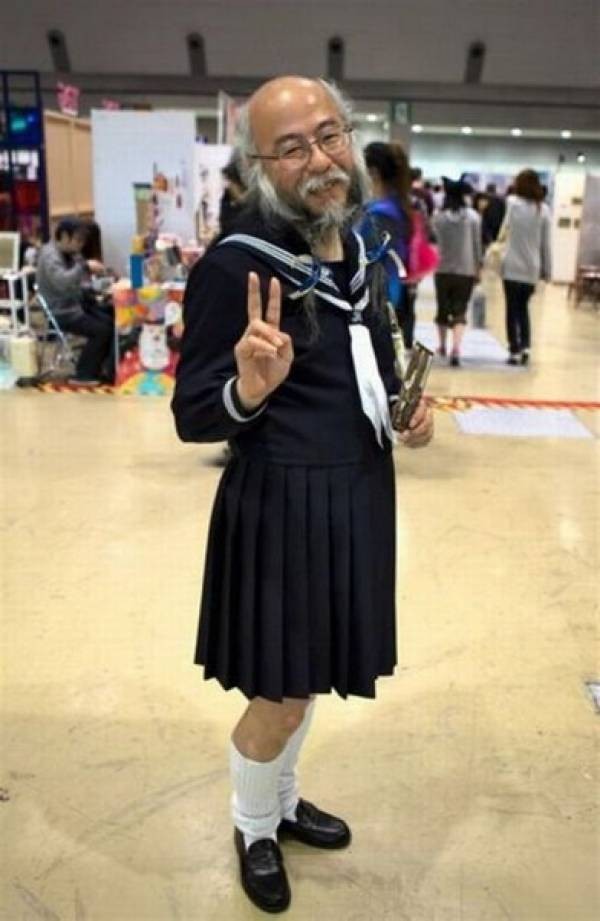

Now, the difference between the groups that are and aren’t “communities” can be quite subtle (an oriental might find it inscrutable). So: homosexuals (of both sexes), bi-sexuals, those who’ve been operated on to change their sex and those just who aren’t sure what theirs is make up such a community, “the gay, lesbian and transgendered community”. And Gill couldn’t possibly say about them the sorts of thing he says about the Japanese. Of course, the English who are sexually modest or reticent or who think homosexuality anything but utterly and perfectly normal aren’t “a community”, so, about them, he could say whatever he liked (and get praised for being “edgy”).

And then, as modern Britain has large minorities (communities) from Africa, the Caribbean and the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent and laws against saying things that might stir up racial hatred, he couldn’t possibly say about Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus or anyone with a black or brown skin (not even those who do torture and murder children for practising witchcraft) the sorts of thing he says about the Japanese. And (even though, by and large, other white, Europeans living in England don’t constitute “communities”), for related reasons, he couldn’t talk about any of what used to be our “partners” in the European Union the way he does about the Japanese either. He couldn’t say, for instance, that, on the whole, if you asked him, with the benefit of hindsight and all things considered, the fire storm that destroyed Dresden was a good thing because it kick-started the modern German economy.

A great many peoples of the world, both in and outside England, are what you might call (by analogy with pandas or whales) “protected species”. The Japanese are not amongst them. Other peoples — the Uzbekistanis or the Peruvians, say — the English are not interested in. The Japanese — because of the second world war and the importance to the British economy of their car plants — aren’t in this group either. So there you have it: they are, for English newspapers, perhaps uniquely, fair game.

We shan’t cease to be interested in them but they could try to get on our list of protected species. How? By migrating here in large numbers and becoming “a community” themselves.