If you watched all of Mark Passio’s seminar on Natural Law which I referred to in Part One, well done. It’s an excellent place to start for an understanding of why Natural Law sits at the top of the Hierarchy of Jurisdiction. You could equally and just as profitably have taken a look at the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas encapsulated here.

“Consequently, every human law has just so much of the nature of law, as it is derived from the law of nature. But if in any point it deflects from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law.”

Hidden in the mists of time, men and women living in tribal groups would have gradually evolved codes of behaviour which would ensure their peace and liberty as individuals and communities. They would have developed an understanding of what is right and what is wrong and of how to exist withing a group without being attacked or, worse, killed. They would have understood that no one has a right to dominate or rule others or to seize more of the bounty of creation than others. This is not innate; it has to be learned, as any parent with a demanding toddler will be able to testify. It is learned from others and, for a code of behaviour to be learned, it will have to exist already in the minds of the elders in a group and in the customs they construct.

Inevitably, given the variation in size and strength between individual humans the strong will be tempted to dominate and exploit the weak simply because they are able to. People will have naturally looked towards certain elders among them, or perhaps to one particularly strong and virile elder, to devise and enforce the rules by which they lived. Kings or Governments were thereby born. If we ask ourselves what came first, people or governments, the answer must be self-evident. Governments were conceived by people in order to bring order to and regulate their existence, to serve and protect the people over whom they are placed. Governments, therefore, must be just and benevolent and exist to serve and protect the people.

It hasn’t worked out very well.

In Part One of Common Law, I introduced the late Karen-Ruth Skölmli and her unfinished on-line course, Sovereign Natural Empowerment. It’s been a few weeks since I wrote Part One because I found some more rich seams to mine and needed to do more digging. Having done so, in Part Two I’m going to try to put a little more meat on the bones in an attempt to explain how this all comes together to form the Ancient Laws and Customs which have come to be known as Common Law.

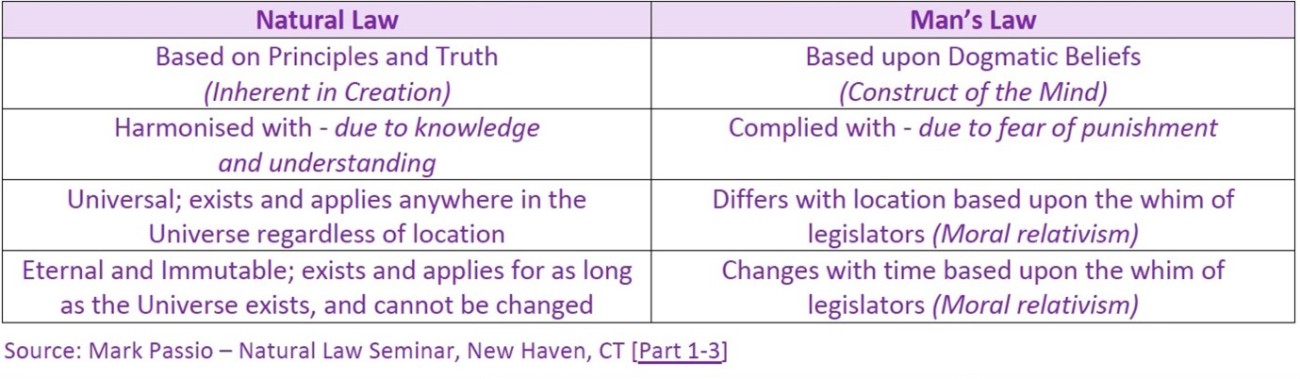

In the Hierarchy of Laws, Natural Law sits at the top. That is indisputable. It is what governs the entire universe, the whole of creation, and it is both unchallengeable and immutable. Below that come the Laws of Man and Woman which have their origins in the time before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings and Normans in the British Isles.

This table explains the essential difference between Natural Law and Man’s Law which cannot do anything but comply with Natural Law.

The most ancient roots and understanding of Sovereignty, Justice and Freedom are most deeply embedded in Ireland. The names for Ireland - Érin, Éirann, Éire are derived from Ériu, the Matron Goddess of Ireland or Goddess of Sovereignty. This is the land of the most ancient law system in Europe , Dlí na Féine, the Law of the Free where Féine is Freeman, Free women or Freeholders in ancient Ireland, also known as Féinachtas and later Brehon Law. This was deeply understood by every man and woman. The Rev. Dr Malcolm in Letters and Essays in 1744 wrote:

“The Celtic language is the key to the antiquities, languages and laws of the entire of our globe.”

That could be a bit of an exaggeration, but it could certainly apply to the European world. Dlí na Féine (the Ancient Law of the Free), Féineachtas, and eventually Brehon Law are referred to in the pre-biblical writings of Lébor Gabála Érenn in the ancient written language of the Gael, Ogham.

Originally law in Ireland was an oral tradition in which all hear the evidence - ‘hearings’. Harm caused to any man or woman was resolved through ‘hearings’ with evidence and witnesses. Mediations and reparations were decided, and no prisons or ‘police’ were required. This law and justice were well known in antiquity when men and women travelled safely and freely in a period when Ireland was known as the Sacred Island.

In Pre-Roman Britain there was much contact, trade and migration across the Irish Sea between Ireland and those parts of Britain now known as Cornwall, Wales, Cumbria, Ayrshire and the Isles of Scotland. The Irish Sea was the great thoroughfare of a Celtic world. These people took their ideas and customs with them as they traded and mingled with the local tribes.

The Romans arrived in AD 43 and started to impose their idea of order. The Roman custom was generally to leave the locals to get on with their lives in their own way so long as they coughed up their taxes when required and generally worked to the greater benefit of Rome. There were rebellions (e.g.Boudicca and the Iceni), but for the most part, Britons took to the Roman ways, adopted their technological advances and learned Latin. Eventually, the most important overlay to this was Christianity when it was adopted by the Emperor Constantine. Christianity was taken to Ireland too once it had taken root in Britain. Christian missionaries, notably St. Patrick, converted the Irish tribes in fairly short order in the fifth century AD.

Trouble back in Rome led to the legions departing in 410 AD and a growing influx of pagan Angles, Saxons and Jutes changed the cultural landscape. Christianity survived in the Brythonic West in what is now Cornwall, Wales and Cumbria but it was all but extinguished in the heart and East of Britain by Anglo-Saxons and later Vikings. Ireland, meanwhile, had become the fabled Land of Saints and Scholars from which Irish missionaries would travel to re-Christianise Eastern Britain. The missionaries established monasteries and abbeys, notably first at Iona and Lindisfarne before moving out and Southwards to York, Chester and Canterbury.

During this ‘Dark Age’ period much of Britain was divided up into separate Kingdoms formed by the Britons, Celts, Picts, Anglo-Saxons (the Heptarchy) and Danes. Ancient laws and customs transitioned from being oral recantations to being written by Brythonic (Welsh) and Anglo-Saxon Kings. It began as early as 450-470 AD when Molmutius (Dyfnwal Moelmud), reputed to be the grandson of Coel Hen (Old King Cole), of Yr Hen Ogledd (The Old North), codified the Molmutine Laws.

The Molmutine Laws were most famously described by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae and again much later by the jurist Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) when he wrote:

“The Molmutius Laws have been always regarded as the foundation and bulwark of British liberties.”

Little remains known of these laws, with surviving Welsh codes simply noting that Dyfnwal's laws were largely superseded by the new codes instituted by Hywel Dda (Howel the Good), King of Deheubarth and eventually most of Wales until his death in 950 AD. Hywel was said to have retained Dyfnwal's units of measurement.

As for the Anglo Saxons at this time, many kings of the Heptarchy issued their own ‘dooms’ or ‘domes’. The Textus Roffensis (Tome of Rochester), written between 1122 and 1124, tells us about them. Most important among them were the The Dooms of Ine, King of Wessex (670-728 AD) which are not specifically listed because they were incorporated in the Domboc of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (849-899 AD) which also incorporated Mosiac Laws.

There is a belief that King Alfred was influenced by the Féineachtas from Éire. He may or may not have been but what is certain is that Alfred was greatly influenced by, and had a high regard for, the Brythonic (Welsh) monk Asser from St.Davids who became Bishop of Sherborne. Asser would certainly have been familiar with Irish laws and customs.

Under the Saxon organisation of England, each county or shire comprised an indefinite number of ‘hundreds’, each hundred comprising groups of ten tithings of ten families of freeholders. The hundred was governed by a chief who could convene his own court. The remarkable thing about them was the common responsibility for the crimes or defaults of individuals. This is thought to have been introduced by Alfred, but it is almost certain that the system was also known among ancient German and Danish people.

Assemblies (moots) were given specific names depending on the type of assembly, place and matters addressed with members called by the sound of the mote-bell. The Anglo-Saxon kings held great councils called Michel-gemot and Witanagemote, later known as Magnum Concilium, the forerunner to Parliament . These communities were self-governing and would elect public officials and create courts to hear disputes and accusations regarding folc-right between members. These were not courts of record for no written record was taken.

Folc-land was the property of the community. It could be held in common or possessed severally or individually by people in the folc-gemote, a general assembly of people of a town or shire. However, it could not be alienated and on the demise of the term for which it had been granted it reverted to the community and would be re-allocated by the folc-gemote according to folc-right or:

“Jus Commune, or common law, mentioned in the Laws of King Edward the Elder, declaring the same equal right, law, or justice to be due to persons of all degrees” (Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780), jurist and politician).

Historical sources describe how the gemote formed courts of freemen who were duty-bound to act as jurors and judges. Duodecima manus (twelve hands) formed the Trial by Jury which would determine the facts and come to a judgement. There was also a Jury formation where a defendant did not speak Anglo-Saxon (Welsh? Cornish? Gaelic?) known as de medietate linguae, half of one tongue, half of the other. Used in both civil and criminal cases, it was composed of six Anglo-Saxon denizens and six of the defendant’s own countrymen, a denizen being a person who may be alien by birth but who has obtained a letter making him a subject of the Anglo-Saxon kings. .

By the end of the reign of Edward the Elder the various folc-gemote were well-established and Witangemote (abr. Witan) were held as the kings required or at their pleasure. This was the way England was run for the next one hundred and forty years.

Then William the Conqueror arrived at Pevensey Bay.

The Conqueror’s victory at Hastings in 1066 was followed by the greatest land-grab in the history of the British Isles. He confiscated the estates of the Anglo-Saxons and introduced a new tenurial system under which he owned all the land. He kept some of it for himself, gave some to the Church and granted the rest to his barons on condition that they swore an oath of loyalty to him and supplied him with men for his armies.

Thus was established the feudal system in England and vast areas of land that were once held in common by folc-gemotes became the fiefdoms of individual nobles; some suitable men became vassals with most lower down becoming villeins. The Domesday Book, ordered by William in 1085 reveals the scale of the Norman land grab. The aggregate value of the area covered by the survey was about £73,000. The Church held some 26 per cent of this territory, but almost everything else was in Norman hands.

The King headed the new “rich list”, with estates covering 17 per cent of England, while roughly 150 -200 barons held another 54 per cent between them. However, there was an elite within the elite. Some 70 men held lands worth £100 to £650, and the 10 greatest magnates controlled enormous fiefdoms worth £650 to £3,240.

The remaining 7,800-odd landholders possessed relatively modest estates. More than 80 per cent of the secular (as distinct from clerical) subtenants named in Great Domesday held lands worth £5 or less. Most of these people were also Normans.

Anglo-Saxon subtenants, by contrast, held only 5 per cent of the country – and the majority of them held just one manor. Some were survivors who had managed to cling to their ancestral estates while others had supported William and prospered under the new regime.

It is tempting to assume such an upheaval in land ownership would completely change the ancient laws and customs long established in Britain, but they didn’t. The changes at first applied only to England and it would be some time before the Normans and their successors, the Plantagenets, would turn their attentions to Wales and Scotland where older ways still survived. Later on, Welsh and Scottish monarchs took the throne of England (Tudors and Stewarts), bringing with them long memories despite their obvious adoption of Norman ways. Besides, there were senior jurists who still knew the ancient laws and customs.

Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) has already been referenced. He was a prolific advocate and practitioner of Common Law. A Barrister, Professor of Law, a Judge, a Member of Parliament, and as Solicitor General, as Attorney General and as Lord Chief Justice appointed by both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I and VI.

From Coke’s Institutes:

“The Common Law is sometimes called, by way of eminence, “lex terrae” as in the statute of Magna Carta chap. 29, where certainly the Common Law is principally intended by those words, aut per legem terrae; as appears by the exposition thereof in several subsequent statutes; and in particularly the statute of 28 Edward III, chap. 3, which is but an exposition and explanation of that statute. Sometimes it is called lex Angliae, as in the statute of Merton, chap. 9 ‘Nolumus leges Angliae non mutari’, etc (We will that the laws of England be not changed). Sometimes it is called ‘lex et consuetudo regni’ (The law and custom of the Kingdom); as in all commissions of oyer and terminer ; and in the statutes of 18 Edward I, and de quo warranto , and divers others. But most commonly it is called Common Law, or the Common Law of England; as in statute Articuli super Chartas , chap.15, in the statute 25 Edward III, chap. 5(4) and infinite more records and statutes”.

There were several other jurists with similar standing to Sir Edward Coke who are on record as expressing themselves on the nature and origins of the term Common Law. Two of them are Sir Matthew Hale (1609-1676) and Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780).

Sir Matthew Hale when Lord Chief Justice of England in Hale’s History of the Common Law p128:

“The Common Law is sometimes called, by way of eminence, “lex terrae” as in the statute of Magna Carta chap. 29, where certainly the Common Law is principally intended by those words, aut per legem terrae; as appears by the exposition thereof in several subsequent statutes; and in particularly the statute of 28 Edward III, chap. 3, which is but an exposition and explanation of that statute. Sometimes it is called lex Angliae, as in the statute of Merton, chap. 9 ‘Nolumus leges Angliae non mutari’, etc (We will that the laws of England be not changed). Sometimes it is called ‘lex et consuetudo regni’ (The law and custom of the Kingdom); as in all commissions of oyer and terminer; and in the statutes of 18 Edward I, and de quo warranto, and divers others. But most commonly it is called Common Law, or the Common Law of England; as in statute Articuli super Chartas, chap.15, in the statute 25 Edward III, chap. 5(4) and infinite more records and statutes”.

Sir William Blackstone in Blackstone’s Introduction to the (Great) Charters, Blackstone’s Law Tracts p 289:

“It is agreed by all our historians that the Great Charter of King John was, for the most part, complied from the ancient customs of the realm, or the laws of Edward the Confessor by which they mean the old Common Law which was established under our Saxon princes”.

That’s pretty clear then. Common Law has been defined by legal luminaries some centuries ago. Why have we not been told about it? What has happened?

In court hearings today decisions and judgements made under statutory legislation have generally been referred to as ‘case law’. However since the late 1960s students of law have been told that this judge-made law is common law or stare decisis (stand by the decisions). Lower case is used in describing it to set it apart from Common Law. Thereby each case decision sets a precedent in the subsequent application of the law. Under Common Law, judgements are reached by a jury, in a lawful Trial by Jury, not by the individual identified as the ‘judge’ within the court system. Hearings under Common Law are before a Jury of twelve and convened by an elected chief or elder whose sole role is as convenor and who has no part in reaching a judgment. This distinction is important as our constitution as reflected in Magna Carta and repeated in the Declaration of Rights, commonly known as the Bill of Rights 1688/89, refers only to our rights and liberties being reduced or impinged upon as a consequence of a lawful Trial by Jury. That is no longer what happens, and it hasn’t been for a very long time.

Next – Magna Carta and Real Democracy