In the early hours of 10 November 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II boarded a train and left Germany for ever, slinking off to Holland. He left Germany in chaos. Revolution was in the air. Sailors of the German Navy had mutinied on being ordered to sea on a suicide mission, and the communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht had proclaimed a Socialist Republic in Berlin.

The ordinary Germany people were near starvation because of the Royal Navy’s blockade and the failure of the German government to plan properly for a long war. The Great War, the War to End All Wars, was in its final couple of days.

The German Army had been beaten mainly – though by no means only – by the efforts of the British Army (which included the well-regarded Empire units from Canada, Australia and New Zealand).

Everybody has heard of the Battle of the Somme, most of the Battle of Passchendaele, and some of Loos - all fixed in the collective mind as disasters, with brave Tommies walking into hails of machine gun bullets or drowning in waist deep mud. Leaving aside the large dollop of myth the collective mind has collected, this article is about a forgotten battle, bigger and far more decisive than these, the Battle of The Hundred Day Offensive, in which the driving force was the British Army.

By the end of 1917 Tsarist Russia had collapsed into a Bolshevik revolution and Germany, in the form of the Treaty of Brest Litovsk, had imposed a punitive peace far worse than the Treaty of Versailles later imposed on it, effectively annexing large parts of Ukraine to gain access to food desperately needed in Germany.

The German High Command, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, referred to as the ‘silent dictatorship,’ knew that they needed to finish the war before the USA could play a decisive part. They did not rate the badly led and hastily put together American Army, which in truth played a minor role in the fighting and was as much a burden as anything else, but they knew that given time and experience, it would grow to be a decisive force sometime in 1919.

The Germans therefore transferred 52 divisions from the East, boosting their strength to 192 divisions, or approximately 3.5 million men for a major onslaught against the British army, by then Germany’s major opponent, at the juncture between the British and French armies, where the British had just taken over from the French, still recovering from the mutiny of their Army in 1917. As Ludendorff noted: "We must strike at the earliest moment before the Americans can throw strong forces into the scale. We must beat the British."

The Germans called it the Kaiserschlacht and launched it after a short but very intense bombardment of the thinly held British lines, kept deliberately short of men by Lloyd George, in dense fog on 21 March 1918. At 04:40, 6,600 German guns and 3,500 mortars opened up a devastating hurricane bombardment across a 40-mile front. In five hours, German batteries fired over 3.5 million shells, the greatest concentration of artillery fire in history up to that point.

Under cover of dense fog German troops surged forward, to find the British lines pulverised and most of the defenders dead. There is much nonsense written about German infantry tactics at the time, with stories of stormtroopers and use of infiltration tactics as if they were something new. They were not.

The differences on 21 March 1918 were that the British were busy adopting the German ‘defence in depth’ system, only partly understood at that time, the dense fog and the exceptionally well-planned intensity of the German bombardment. The effect was devastating, and the Germans achieved an unprecedent break in.

But they paid a high price, losing many of their best men, as pockets of British infantry and the remaining artillery held out, often fighting to the last man. The weakened British were forced to retreat, but the Germans failed to achieve the hoped-for breakthrough, the British carrying out a fighting retreat, inflicting heavy casualties on the Germans as they went.

An example is the stand on Manchester Hill, an important defensive position given its name after being captured in 1917 by the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment, which included the poet, Wilfred Owen.

On March 21 Manchester Hill was defended by the 16th Manchesters, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Wilfrith Elstob, a teacher and vicar’s son who, although a graduate of Manchester University, had joined up as a private on the first day of the war. They now faced an overwhelming superiority of infantry and artillery.

Elstob told his men “Here we fight – and here we die.” The German attack was preceded by a storm of artillery fire, both high explosive and gas. Despite most of his men being killed or injured, and he himself wounded three times, he maintained that ‘the Manchester Regiment will defend Manchester Hill to the last.’

Elstob was shot again and killed. Of the 168 men who fought to defend the position, only seventeen managed to return to the British Lines. Seventy-nine were killed and most of the rest wounded and captured by the Germans.

Lieutenant Colonel Elstob was awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry, adding to his Distinguished Service Order and Military Cross.

The British defence, reinforced by the French, meant that the Germans did not achieve the breakthrough they had hoped for, instead creating an awkward salient. By 5 April, the offensive was halted. But they had planned a further offensive further north, in what both they and the British considered the crucial sector in Flanders, around Ypres. The attack there, on 9 April, was made against the Portuguese-held part of the line. The wretched Portuguese were swept away, the Germans punching a 30-mile-wide hole in the allied line.

This was plugged by the British, with French and Belgian help, and the German’s northern offensive withered away, to be followed by local offensives. But it was becoming apparent that the German army, which had lost more men than the British and French combined, had almost worn itself out.

Nevertheless, on 27 May, the Germans made yet another attempt to break the deadlock, attacking the French line in a quiet sector partly held by worn out and shattered British divisions, sent there to recover. The Germans pushed the French and British back ten miles, but again the line held, and the Germans found themselves in yet another dangerous salient.

The German’s final attempt to win the war came on 15 July, against the French, who fell back a little and then held. The French even carried out a successful counterattack. The tide had finally turned and soon it would be the Germans retreating, a retreat that carried on till the last day of the war.

The British army was also weakened with the average division reduced from twelve to nine battalions (though Australian and Canadian divisions, often reinforced with British battalions, had been kept at full strength on the demand by their governments), with battalions reduced from about 800 to 650 men.

But the British Army had developed its own tactical innovations, the All-Arms battle, latter copied by the Germans in 1940. British soldiers were not just armed with rifles, they had large numbers of relatively easily carried Lewis machine guns, any amount of hand grenades and rifle grenades, giving a British platoon almost as much firepower as a 1916 company. This was backed up by the heavy Vickers machine guns of the Machine Gun Corp, which had developed a highly effective barrage, firing over the heads of advancing British troops to supress German defenders.

The First World War was an artillery war, and by mid-1918 the British artillery dominated. British manufacturing had surpassed itself and there was unlimited availability of all types of shells, including gas shells used to supress German defence. The artillery had mostly abandoned the give-away preliminary bombardment, and was shooting from map references, concentrating on German artillery, strong points and communications centres, all spotted by the new RAF (formed 1 April 1918 from the Royal Flying Corp and the and the Royal Naval Air Service) which had almost complete air superiority, engaging in both infantry support and strategic bombing.

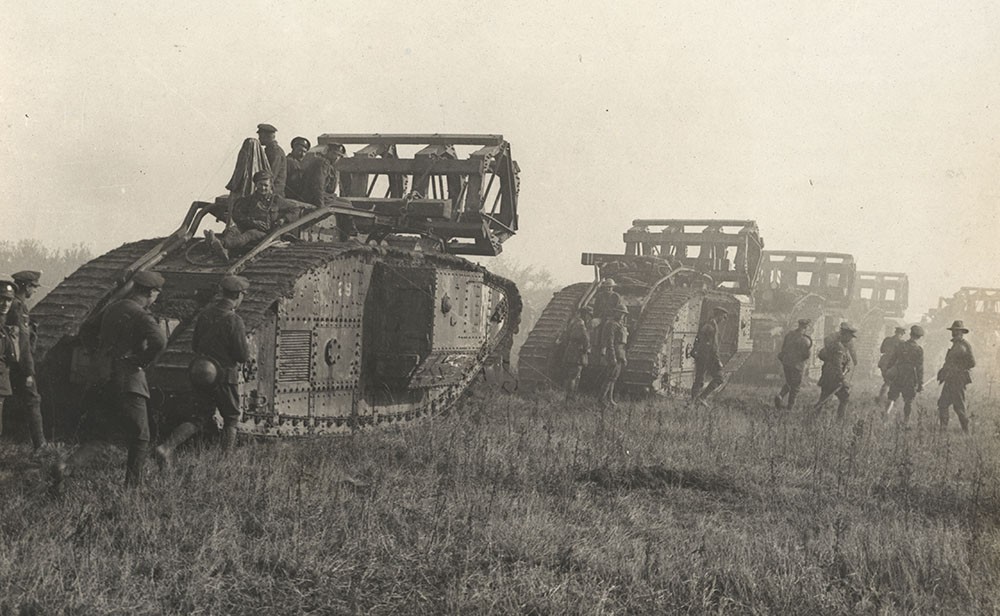

And finally, the Tank Corp, now equipped with a variety of tank types – including male and female – had more reliable and faster tanks, and had developed much more effective tactics, honed at Cambrai in November 1917.

The scene was set for one of the most impressive feats of arms ever carried out by the British Army – the One Hundred Day offensive that brought the War to End All Wars to an end. The new All-Arms tactics were first tested in an attack on Hamel on 4 July 1918, causing the demoralised Germans to surrender in droves. British casualties were 1,400, but the Germans lost about 3,500 – good odds in attritional warfare.

And so, both sides prepared for the next stage. The Germans now fully aware that their gamble had failed and that the best they could hope for was to hang on to their gains and rebuild their army behind strong defences. The British prepared to go on the offensive, with a plan to attack Amiens on 8 August 1918 – later described by General Ludendorff as the "Schwarzer Tag des deutschen Heeres" - the "black day of the German Army."

One innovation was what now is the obvious involvement of experts from all branches – and the fact that they were listened to. For example, Lt. Colonel Fuller of the Tank Corps objected to only six tank battalions being allocated to the assault. He insisted that the whole Tank Corps of twelve battalions be used, bringing the total number of tanks to 540, making this the biggest tank battle of the war, with tanks fully integrated into the All-Arms battle plan – a tactic the Germans of 1940 are usually credited with.

Also, the stated philosophy of the battle was ‘firepower not manpower’ the main aspect of which was artillery, with British gunners having achieved a complete theoretical and practical grip on the science of gunnery. There would be no preliminary bombardment, and their main target would be German artillery, which would be drenched with a torrent of gas and high explosive shells to prevent them from firing at the advancing British infantry. At the same time, as the infantry attacked, they were sheltered by a creeping barrage by the field artillery moving forward a hundred yards or so in front of the infantry, keeping German machine gunners under cover.

Advanced survey and arial techniques had revealed the location of 504 of the 530 German artillery pieces in the area, the Royal Artillery deploying 1,386 field guns and howitzers and 684 heavy guns against them. The RAF had over eight hundred aircraft, scouts, fighters, bombers and long-range reconnaissance aircraft, against 365 German.

And then came the infantry. Small groups of advance scouts, working with the tanks just behind the creeping barrage, would identify surviving German machine gun posts and set the tanks on them. Behind this was the main body, attacking at section level in ‘worms’ of eight men. And behind this support battalions would advance in open formation – as tactically skilled an attack as anything seen up to then and comparable with the best of WW2 infantry tactics.

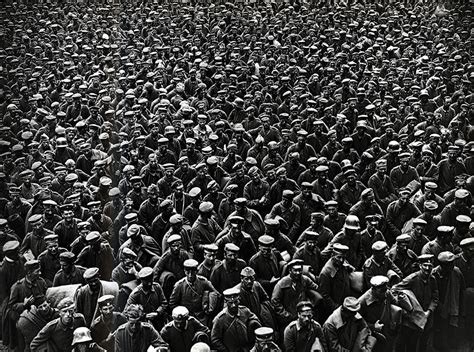

In the event, it was an incredible success. The German artillery was overwhelmed, and the British advanced eight mile on a ten-mile front, the Germans suffering 27,700 casualties, including 15,000 prisoners, as well as losing over four hundred guns and large numbers of mortars and machine guns. The British suffered ‘only’ 9,000 casualties. The attack was stopped after three days, when German resistance stiffened.

Further offensives began on 21 August by the British Third Army, and then First on the 28th, keeping the Germans under pressure. This kept on right to the end; relentless attacks all along the line, with the Germans not knowing where they would be attacked next.

What was meant to be the final push was started on 26 September, led by the fresh but inexperienced US Army, commanded by possibly the worst general of the war, Pershing, who persisted in attacking strong points instead of by-passing them. The Americans waited for mist to clear instead of using it for cover and, too often, discipline broke down. The US Army suffered over 10,000 casualties and advanced only eight miles in over a week’s fighting against the much-weakened Germans.

At about the same time, a most impressive feat of arms was carried out by the 46th (North Midland) Division, spearheaded by the 137th (Staffordshire) Brigade, in the crossing of the St Quentin canal, one of the most heavily defended stretches of the formidable Hindenburg Line,. The objective to was capture and secure the canal, assault the Hindenburg Line and capture four strongly defended villages all formidably defended with concrete machine gun posts, deep dugouts and barbed wire.

The canal was 35ft wide and up to 10ft deep. Men were given a lifebelt that could be worn by a soldier laden with equipment, so long as the weight was distributed across the lower parts of the body. Collapsible boats, ropes and ladders were also provided.

The assault was preceded by a bombardment by Allied artillery, consisting of 1,044 field guns and howitzers and 593 medium and heavy guns, which commenced at 22.30 on 26th September. The bombardment ensured that the Germans were forced to stay in their defensive positions and make their resupplying almost impossible. The routes used to resupply were targeted intensely, resulting in a lack of ammunition and food being brought to the Germans in those positions. The bombardment lasted right up until Zero Hour on 29 September.

At 0550, Brigadier-General John Campbell VC, the commander of the brigade, led his unit from the front, blowing his hunting horn. The whole of the first line of German positions was taken very swiftly, with few British casualties and the capture of 150 prisoners. Additionally, 1,000 Germans were discovered to have been killed by the bombardment.

The canal was crossed by many means. In the southern sector, where the canal was shallower, the provided rafts and ropes were used, as was a small wooden bridge left intact by the Germans. Some soldiers swam across the icy water, not realising that there was a bridge until after they had done so. Officers swam across the canal with ropes, and then pulled some men over on rafts and boats. As soon as they had crossed, ascents were made up the east bank, the Germans firing on them with machine guns, but despite carrying heavy equipment and being soaking wet, they managed to overrun the German positions.

It was at this point men from the 1/6th North Staffords, led by Captain A.H. Charlton, rushed the still intact Riqueval Bridge – the largest in that area – and overwhelmed a machine gun post on the east bank. Captain Charlton then cut wires to the explosives around the bridge that a German demolition team were about to detonate, and threw the charge into the canal. His group then secured a bridgehead and 130 prisoners were captured, including a senior German officer and his staff.

For his role in the action, Captain Charlton was awarded the D.S.O. The capture of this bridge was incredibly important as it became become a significant route in furthering the advance and allowing the army to be re-supplied.

By 0830, the 137th Brigade had captured the St Quentin Canal from Bellicourt to Bellenglise, including the Riqueval Bridge, and had reached the second section of the Hindenburg Line. By the end of the day the 46th Division had taken 4,200 German prisoners and over seventy guns and had met all of its objectives, on schedule, at a cost of fewer than eight hundred casualties to the division, achieving an objective many considered impossible.

The breaking of the Hindenburg Line was absolutely critical in bring about the end of the war, and the armistice would be signed six weeks later.

By this time the Germans knew they were beaten and had approached the US President, the untrustworthy Woodrow Wilson, a ‘progressive’ self-righteous idealist who, without consulting his allies - who had done and were still doing most of the fighting - came up with a 14-point plan for an idealistic peace – which met opposition from all parties, including US General Pershing, who wanted the fighting to continue to give his relatively untried army a chance of success.

While the political wrangling went on, so did the fighting and killing. The last Allied offensive began on 4 November 1918, when the British First, Third and Fourth Armies attacked on a 40-mile front, through dense woodland and across the Sambre Canal. Thousands of German prisoners were captured, and the tired men of the British Army began to suspect that the German retreat was becoming a rout, and that the end was in sight.

This makes the death of men killed in this period especially poignant. And there were many. One death occurred on the cold morning of 4th November, when the 2nd Manchesters were crossing the Sambre Canal. The death was that of a young officer, previously awarded the Military Cross, shot down by German machine gunners while urging his men forward. He was 25-year-old Wilfred Owen, whose poems ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ and ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ came to define the Great War in the popular mind.

On 7 November, the Germans had asked for a meeting with the Allies, which occurred the next morning in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiegne, the Allies represented by Marshal Foch and the Royal Navy’s Admiral Wemyss. The terms presented to the Germans were harsh, but the revolution in Berlin and the parlous state of Germany and her army gave the Germans little negotiating leverage and an armistice – a ceasefire, not a peace agreement - was signed at 5 a.m. 11 November. At 11 a.m. that morning, the fighting stopped, and the guns fell silent. The Great War was over – and the world would never be the same again.

The British Army suffered approximately 420,000 casualties during the Hundred Day Offensive.