These days it’s easy to sit around feeling upset and angry about the incessant attacks on our British culture and history or even our very identity. A common recourse for many (me included if I’m honest) is to take to social media and/or chat forums and share thoughts and feelings with others of a like mind. That might be a suitable safety valve, but it is hardly doing anything positive to defend our heritage.

Within our own homes and families and while we are out and about, we can cleave to what is traditional and support the good, the true and the beautiful by enjoying real art forms as opposed to the modern garbage which is passed off as “art”, whether it be written, painted, sculpted, “installed” or supposedly musical. But wouldn’t it be even better to take part ourselves in something which is viewed as a part of traditional British culture? To do one’s bit to help keep something going which might otherwise be seen to be undergoing a slow, protracted death?

So, what might one do? Morris dancing? Take up the bagpipes? Join a Welsh male voice choir? No, none of that. What has happened to me is that I have become a church bellringer, a campanologist - and I am really quite enjoying it.

How did this come about? Well, just before Christmas in 2022 an email popped into my inbox drawing my attention to an appeal on the Nextdoor Neighbourhood website. Somebody was seeking people who might be interested in having a go at learning to ring the bells in our local parish church, St Michael and All Angels. Over the years I had often listened to the bells being rung for services, weddings and on other occasions but, I have to confess, I had failed to notice that they had fallen silent in recent times. Because of the lockdowns and church closures the ringing had ceased but it had not registered with me that the bells had failed to restart in their former glory once the church was open again.

Although I retired in 2016, I had been working for myself as a pilot training consultant which kept me in touch with my previous life as well as topping up the pension. However, the lockdowns forced final retirement on me. Since then, I had been looking for things to fill my time and I thought, well, why not? I could at least go and have a try, and my wife agreed. So it was that I found myself climbing the spiral stone stairs up to the belltower ringing room at the village church on a wet and windy January night in 2023.

What had happened was that where once there had been a group of more than a dozen ringers, the lockdowns had ended the participation of many of them. Some moved away, others gave up and some simply felt they were now too old. It left a core of three. Fortunately, two of them were very experienced bellringing teachers, a husband and wife who are a church chorister and an organist. It was around this couple that we neophytes gathered. I was not alone. Six or seven others had answered the call and were, literally, being shown the ropes.

I had seen the odd snatch of bellringing on the television from time to time and rather idiotically thought it was a simple matter of pulling on the end of a long rope in some sort of order. Not so. There is more to the ringing of church bells than meets the eye. A lot more.

The first thing to understand is that there are safety rules which have to be followed. Church bells are serious lumps of metal and injuries, or worse, can occur if things go wrong. No doubt most people have seen cartoons of bellringers being hoist to the ceiling by their bell ropes but believe me, it does happen. I’ve seen it. When a bell is up at the inverted position is rests on a ‘stay’. If the stay breaks there is nothing to stop it going over the top out of control and that is when the rope will be whipped up smartly. If you don’t let go of the rope instantly - up you go. Then you have to keep hold until the bell swings back and lets you down; it could be a long way to the floor otherwise. When ‘sitting out’ you keep your feet flat on the floor; crossing legs is out in case a rope gets wrapped around your foot or ankle. And never let your hand go through the loop at the tail end of the rope. One never goes up into the bell chamber when the bells are ‘up’ and never alone.

Most parish churches have rings of six or eight bells, from the treble, the lightest and highest pitched, to the tenor, the lowest and heaviest. Ours has eight, tuned in D, with the tenor bell weighing in at 11 hundredweight (cwt) 0 quarters and 27 pounds. Traditional English weights and measures are used for bells so for those who are unfamiliar with them that’s 1,259 pounds or 572.27 kilograms. Quite a small bell really, as far as bells go. At the extreme end, St Paul’s Cathedral, where there is a ring of twelve change ringing bells, the tenor bell weighs 61 cwt (3.05 tons). That’s a midget compared to the ‘Great Paul’ bourdon bell which is the heaviest church bell in Britain at 16.75 tons.

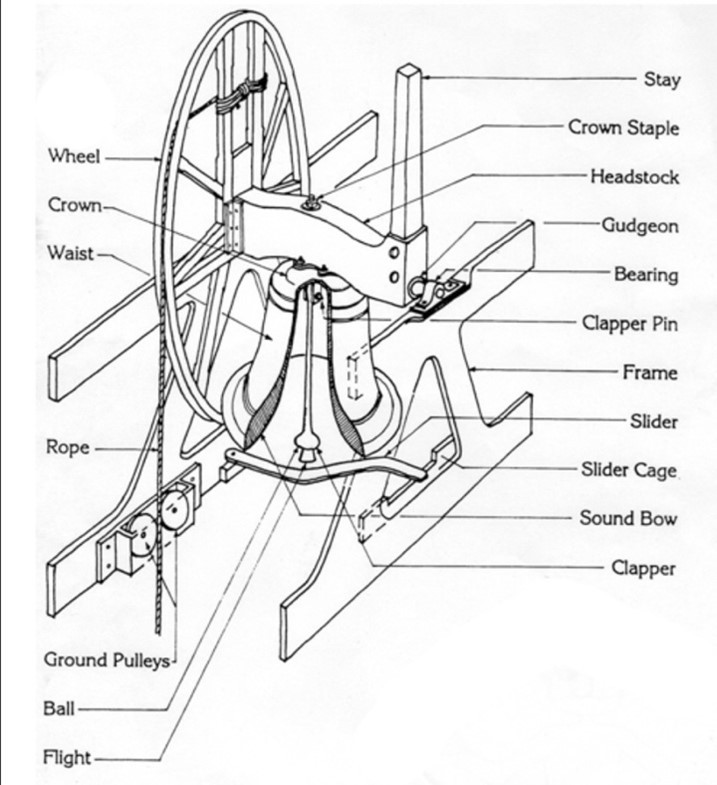

You need to know the various parts of a bell installation and that is done using a diagram, as below, or with a model.

All bells are different. Larger, heavier bells have larger wheels which means they need longer ropes. That means the point on each stroke or pull when the clapper strikes the sound bow and the bell rings will be slightly different; the gap that a ringer leaves between the prior bell before ringing his or her own will need to be shorter the bigger the bell. Ropes also expand and contract a little and harden and soften with temperature and humidity. This all adds to the fun.

The rope has a fluffy coloured hand grip known as the ‘sally’; the other end is called the ‘tail end’. A pull on the ‘sally’ is called a ‘hand’ stroke and the subsequent pull on the ‘tail’ end is called a ‘back’ stroke. Beginners need to learn the correct technique for each stroke in isolation before putting them together. During this they will begin to acquire a feel for the bell they are ringing. For this reason, they are generally taught on the same bell, usually one of the lighter ones. The aim is to get a beginner ringing safely and in control of the bell, not the other way around.

Once that’s done, a new ringer will learn how to ring a bell ‘up’ and ring it ‘down’. A bell is usually ‘down’ to begin with which is the normal hanging position shown in the diagram. A bell is ‘up’ when it is inverted and resting on its stay; this stops it going right over by impinging on the ‘slider’. Our tyro will also have to learn how to slow down and speed up and be able to ‘stand’ the bell (rest it on the stay) at both hand stroke and back stroke. Once accomplished, they can move to heavier or lighter bells to begin to get a feel for the differences. Once this is mastered a beginner can be regarded as a competent ringer ready to join ringing with the rest of the band.

Assuming the bells are ‘up’, all ringing starts with ‘rounds’ when the bells are struck in order, 1 2 3 4 5 6 etc. In this case, a ring of six, the treble is 1 and the tenor 6. The aim is to get the striking evenly spaced and once that has been achieved, learners are ready to move on to ‘call changes’. When ‘rounds’ is being evenly struck, the conductor calls a bell to change position, for example, “2 to 3” which means bell 2 now follows bell 3. There are implications for others: Since 2 now follows 3, 3 follows 1 and bell 4, instead of following 3, now follows 2. The new order is 1 3 2 4 5 6. Ringers have to work out their new position and note which bell precedes the bell they are now following so they know which bell to follow if the bell they are following is called to move. For example, a second call “4 to 5” would result in new order 1 3 2 5 4 6.

This video shows excellent demonstrations of ringing up in peal, call changes and ringing down in peal. Some bell tower bands leave it at that and only ring call changes for which there are a number of standard patterns which have names so the bands can go straight to them. One of the most popular is “Queens” which can be entered direct from ‘rounds’ and is 1 3 5 2 4 6. However, most will use ‘methods’ which can seem quite daunting to a beginner because they have to be learned, and this is where the language of bellringing must be acquired.

Dealing with even numbers of bells first, 4 bells is ‘Minimus’, 6 bells is ‘Minor’, 8 bells ‘Major’, ten ‘Royal’ and twelve bells is ‘Maximus’. For occasions when they are an odd number for whatever reason, 3 bells is ‘Singles’, 5 is ‘Doubles’, 7 ‘Triples’, 9 ‘Quaters’ and 11 bells is ‘Cinqs’. Don’t ask me why. A ‘method’ will be given a name such as Grandsire, Stedman or Cambridge followed by one of these terms which will indicate the number of bells; it may also include the number of changes. For example, 1260 Grandsire Triples is a ring of 1260 changes using the Grandsire method on 7 bells. To be able to do this it has to be learned by each ringer. There is no way around that. There are literally thousands of possible permutations.

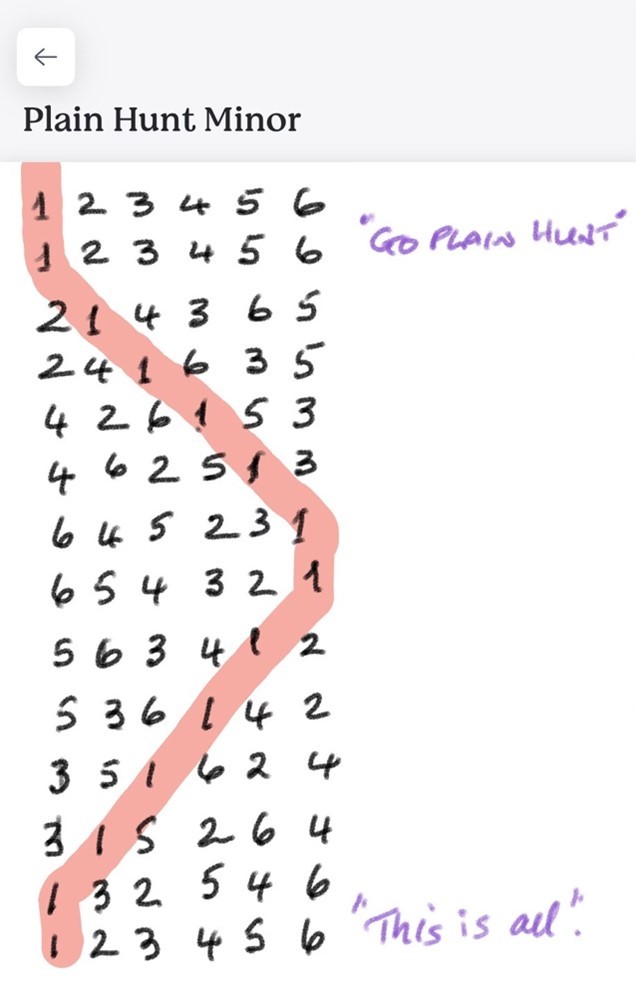

The basis of method ringing is Plain Hunt which has to be mastered so that a ringer can do it on any bell in the ring. In a Plain Hunt, bells swap positions at every stroke unless they are lying at the back (last) or at the front (leading) in which case they do two strokes in each of those positions. This video demonstrates a Plain Hunt Minor (6 bells). It is noteworthy that the pattern is complete in 12 strokes. If it were a Major (8 bells) it would be 16 strokes or a Royal (10 bells) 20 strokes.

Each ringer also has to acquire ‘ropesight’ so that he or she picks up from the vertical movement of the ropes who is following whom. Positions can then be changed without having to use bell numbers or even reverting to peoples’ names. Basically, the person who follows you is the one you will follow at the next stroke. The pattern of rope movement is learned. Here is a diagram of Plain Hunt Minor. The path of the treble bell is highlighted in red.

The paths of every bell can be marked in the same manner. Rather than ending when back in rounds as the band in the video does, Plain Hunt can be continued for as many times as desired. Indeed, the convention is that the band will continue hunting until such time as the conductor calls ‘That’s all” which could be five minutes or half an hour. That makes it ideal for ringing for about 20 minutes or so before a church service.

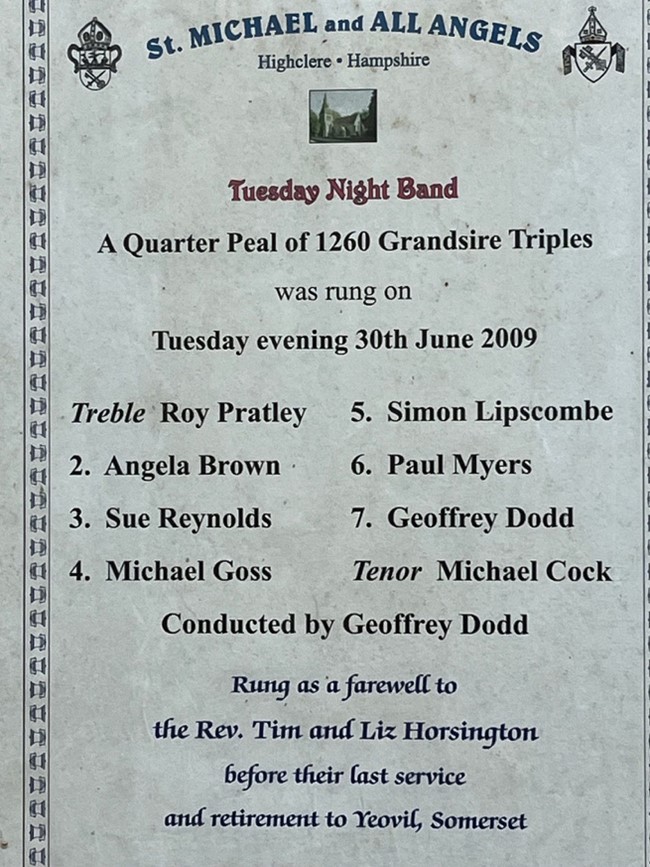

One of the misconceptions that most people have is that the simple ringing of church bells in sequence is a peal. It’s not really the case. A full peal in most methods will last for about 3 hours and will involve thousands of changes! For that reason, it is common to employ a quarter peal for special occasions which generally take about 45 minutes. For example, this certificate in our bell tower marks an occasion when a quarter peal was rung to mark the retirement of a previous very popular rector.

Note that the method was Grandsire Triples but eight bells were rung. In this case that means that the tenor stayed at the back, effectively beating time and only the front seven bells changed positions.

The greatest thing about bellringing is that it is an activity for all. Lots of women do it and children can make a start as young as 9 or 10. There are ringers in their 90s too, so age is no barrier. It’s good physical and mental exercise and it promotes social life, friendship and camaraderie. Our new band has already had two single day tours in each of the last two summers when we visited 6 or 7 towers in Hampshire and Wiltshire to ring the bells. If each bell is different, each bell tower is more so and that in itself can present some interesting variations. We also got together for a Christmas dinner last year and we are planning the same again this year.

This video gives a flavour. So, if you’ve ever thought you’d like to give it a try, get in touch with the Tower Captain at your local C of E church. In case you’re put off by the thought of perhaps having to go to church yourself, don’t be. Plenty of ringers don’t. They just get on their bikes when they’ve finished. It is a service to the church but whether you attend yourself really is up to you. You’d be doing a little bit to keep a centuries-old tradition alive.

Iain Hunter