Today is the anniversary of the infamous attack on Israel by savages from the Hamas terrorist organisation, which not only murders innocent Israelis but also the benighted people of Gaza, who it hides behind after provoking Israel into an armed response.

Perhaps the best way to mark the anniversary is to set out the truth about the formation of the Jewish state and show that it is not a colonial implant, but instead as legitimate a State as any in the region.

My last article on Israel looked at the history of the Jews in the Holy Land from ancient times up to the British Mandate and showed that the Jewish people have always had a significant presence there and have at least as much claim to it as anybody. This article examines what happened from 1916 up the formation of the Jewish State in 1948.

To fully understand the reality of Israel’s creation it is necessary to go back to 1916, when Britain and France divided the Levant between them by means of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which envisioned the establishment of mandates for France in Lebanon and Syria, and Britain in what is now Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan and Iraq, all of which were then under the control of the Turks, who had sided with Germany in the still raging Great War.

Up to 1918, when the war ended in defeat for Turkey and with the British Army occupying nearly all of the Levant, Palestine was a sub-unit of the Turkish vilayet (principality) of Syria, ruled from Damascus, with the exception of Jewish-dominated Jerusalem, which was an independent sanjak reporting directly to Istanbul. The Arab inhabitants, Muslim and Christian, considered themselves to be Syrians and did so right through to 1948, at no time calling for a separate Palestinian state.

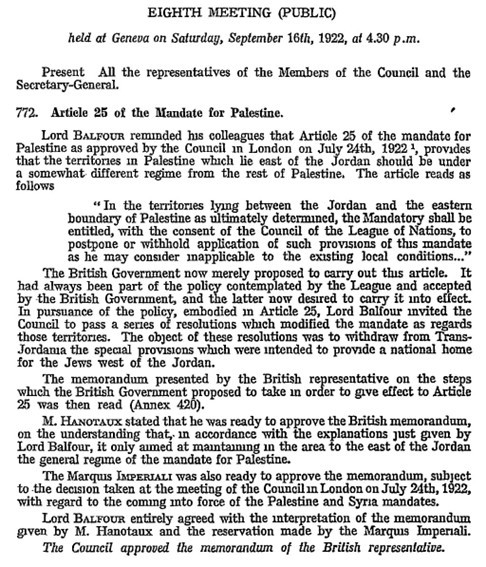

It is important to understand that in 1922 the British divided Palestine, creating in effect a two-state solution - and one very favourable to the Muslim Arabs, who got by far the larger area. This division left the land west of the Jordan, from the river to the sea, as the new Jewish homeland.

The British Foreign Office had pressed what they called the Sharifian Solution, the installation of Hashemite Chiefs (previously the sharifs of Mecca) into the artificially created lands forming the British Mandate. This was first done in Iraq, which need not trouble us further, except to note with interest that, at the time of the Muslim conquest around 800, Iraq is estimated to have had a population of 30 million. By 1918 this had dwindled to about five million. One of the first things the British did in Iraq, in 1920, was to abolish slavery.

The Hashemites had been expelled from what is now Saudi Arabia, but as a reward for help in defeating the Ottomans, Britain promised them crowns further north. Churchill later said that “with the stroke of a pen one Sunday afternoon in Cairo” in 1921, he split Palestine and created Transjordan, now known as the Kingdom of Jordan. Apparently, having been drinking that day, the then colonial secretary’s penmanship was wobbly, allegedly producing a particularly erratic borderline. The resulting zigzag that still delineates the border between Jordan and Saudi Arabia is sometimes referred to as “Winston’s Hiccup” or “Churchill’s Sneeze.”

As well as rewarding the Hashemites, Britain saw Transjordan as a refuelling stop on the way to India and as a strategic asset because of what became the Kirkuk–Haifa oil pipeline.

A British government memo in 1922 to the League of Nations explained the decision to alter the original League of Nations mandate, which had assumed a Jewish homeland in a unitary state of Palestine, as follows:

“Distinction to be drawn between Palestine and Trans-Jordan under the Mandate. His Majesty’s Government are responsible under the terms of the Mandate for establishing in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people.

They are also pledged by the assurances given to the Sherif of Mecca in 1915 to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs in those portions of the (Turkish) vilayet of Damascus in which they are free to act without detriment to French interests. “

The critical fact here is that Churchill’s “stroke of the pen” was in fact a two-state solution, and one enormously favourable to Muslim Arabs. It divided Palestine into two, with roughly three quarters of it – all that east of the River Jordan - going to the Arab state of Jordan, a wholly Muslim country from which Jewish settlement was barred.

This angered the Zionists as it reduced the area available for a future Jewish state, which they had expected to encompass all of Palestine, both sides of the River Jordan, not just ‘from the river to the sea’. Many reminded Churchill of what he had said during WW1, that “It is manifestly right that the scattered Jews should have a national centre and a national home and be reunited and where else but in Palestine with which they have for 3,000 years been intimately and profoundly associated? We think it will be good for the world, good for the Jews, good for the British Empire, but also good for the Arabs who dwell in Palestine….. They shall share in the benefits and progress of Zionism.”

There can be no doubt that by the Balfour Declaration the British, and later League of Nations, had intended that the Jewish National Home was to be established in the whole of historic Palestine, including Transjordan. This was confirmed by the Peel Commission, appointed to investigate the cause of the 1936 Arab riots.

Ironically, it was Lord Balfour, whose letter to Lord Rothschild in 1917 had promised the Jews a national home in Palestine, who told the League that Britain would split Palestine and withdraw Transjordan from the area intended to provide a national home for the Jews.

During the British Mandate (1920-1948), Jewish immigration to Palestine increased significantly, driven partly by the Zionist movement, which sought to establish a Jewish homeland, but more so, since the second Aliyah (1904-1914), by Jews seeking asylum from persecution. The Russian pogroms of 1903-1906 were a major driver of Jewish migration to Palestine.

The Arab population in Palestine also grew at the same time, because of immigration from Egypt, Lebanon and Syria, attracted by the job opportunities Jewish business had created. Up to then the Muslim Arab population of Palestine was in large part a transient and migratory Bedouin population, but the success of many Jewish settlements attracted Arab workers. The Jewish settlement of Rishon L’Tzion, for example, established in 1882 on empty land purchased from Arabs by 40 Jewish families, soon attracted more than 400 Arab families, most of whom were Egyptian or former Bedouin, who then formed their own village. This seems to have been a common occurrence.

According to one historian, Ernst Frankenstein, at least 25% of all the Muslims who lived in Palestine in 1882 were newcomers, and since then there was considerable immigration of Muslim Turks and Algerians. Furthermore, many of the Palestinian Muslims had recently moved from what became Jordan, from east of the river. This leads to the probability that the number of Muslim Arabs with deep roots in what became Israel constituted a small fraction of the Palestinians living in Israel in 1948.

Tensions between Jewish and Arab communities escalated and the 1920s and 1930s saw a series of violent clashes, such as the Jaffa Riots of 1921 and the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939. In these it was usually, but by no means always, Arabs attacking Jews with the Jews responding in kind. A Muslim motto of the time was “Muhammad’s religion was born with the sword.”

Jewish women were raped and synagogues destroyed in a pogrom organised by a group called Al-Nadi Al-Arabi. A British investigation concluded “All the evidence goes to show that these attacks were of a cowardly and treacherous description, mostly against old men, women and children – frequently in the back”.

Many, but not all, Jewish settlers sought good relations with their Arab neighbours, one of whom, Yitzhak Epstein advocated giving Arabs access to Jewish hospitals, schools and libraries. Others advised against buying too much land, especially near Muslim holy sites.

It is worth emphasising that all Jewish settlements were on land legally purchased from Arab owners.

The British government attempted to mediate the conflict through various commissions and white papers, but – typical of British bureaucracy - these efforts were wishy-washy and satisfied neither side, with concessions being given to the side which caused the most trouble, usually the Muslim Arabs. The FO was also instinctively Arabist. The 1939 White Paper, for instance, limited Jewish immigration and land purchases, which angered the Jewish community while failing to placate the Arabs.

To appease the unappeasable, the British started to block Jewish immigration, at one time trying to divert them to Mauritius. On one occasion in 1942, the British refused landing permission to Jewish refugees on STRUMA a ship that had carried them from Romania. She subsequently sank, drowning 770 people.

Inexplicably, the British tried to control the violence by appointing the rabidly anti-Jewish Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, as spiritual head and political leader of Palestinian Muslims in the hope that he would stop Islamist attacks. This was an error almost comical in its magnitude, as al-Husseini was a great admirer of Adolf Hitler and shared his attitude to Jews. When the Second World War broke out he became an ally and advisor to Hitler and preached the ‘final solution’ to his Muslim followers. He assisted in recruiting a Muslim SS Division for Hitler, who admired Islam, and asked Hitler to end Palestine’s Jewish problem ‘in accordance with the racial interests of the Arabs and along the lines similar to those used to solve the Jewish problem in Germany’.

Hitler sent millions of dollars to the Mufti, and SS boss Heinrich Himmler provided financial and logistical support for anti-Jewish pogroms in Palestine. Adolf Eichman visited Husseini in Jerusalem and formed a close relationship.

At the end of the Second World War Churchill said that the Arabs were owed nothing in a post war settlement because of their support for National Socialism and Hitler. In contrast, 5,000 Jewish Palestinians volunteered to fight for Britain and fought with the 25,000 strong Jewish Brigade (which later formed the core of the IDF).

World War II obviously had a profound impact on the Jewish community worldwide. The Holocaust, in which six million Jews were systematically murdered by National Socialist Germany, underscored the urgent need for a Jewish homeland. The post-war period saw a surge in Jewish refugees seeking to escape the devastation of Europe, many of whom aimed to reach Palestine.

By the end of World War II, Britain was increasingly unable to manage the growing conflict in Palestine. At that time the Labour Party, which had formed a new government, was pro-Zionist, but deferred to the Arabist FO in favouring the Arabs, a decision made easier by the rise of highly effective Jewish terrorism in the form of the Stern Gang, one of whose leaders was Menachem Begin, later an Israeli PM, Nobel Peace Prize Winner and a man made ruthless by his experience of WW2, where the German occupation of his home town in Poland, which had 30,000 Jews in 1939 left only ten remaining alive in 1944. Most of Begin’s family were murdered. He was one of the few to survive an interrogation by Stalin’s NKVD unbroken.

So violent were the Stern Gang, who had murdered Lord Moyne, the Minister for Middle East Affairs, that the official Zionist military organisation, the Haganah – which did not employ terror - launched what it called a hunting season against Stern Gang members and another violent Jewish organisation, the Irgun, which had blown up the King David Hotel containing British administrative and military offices, bringing Jews close to civil war.

But Attlee’s Labour government had no stomach for a fight, and 18 months later Bevin threw in his hand, causing Evelyn Waugh to remark “We surrendered our mandate to rule the Holy Land for low motives, cowardice, sloth and parsimony.”

In 1947, the British government referred the issue to the newly formed United Nations. The UN Special Committee on Palestine proposed another partition plan, which recommended the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem under international administration.

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, approving the partition plan. The Jewish community accepted the plan, but the Arabs and surrounding Arab states rejected it, leading to increased violence.

As the British prepared to withdraw from Palestine, the situation escalated into a full-scale war between Jewish and Arabs forces, with attack and counterattack, atrocity and counter-atrocity being carried out by both sides,

While the Jews were still celebrating the UN’s announcement, attacks escalated as Arabs tried to expand their control over Palestine and forestall the creation of a Jewish state. The Arabs enjoyed several advantages over Jewish forces, including a larger population, better resources, and higher ground from which to attack. But members of the Yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine), many of whom had witnessed the Holocaust and persecution in Europe, were highly motivated and not a single Jewish village was destroyed or abandoned to Arab aggression. However, the Arabs were able to control important highways, choking vital supply lines to the Jewish communities in Jerusalem and the Negev.

In April 1948, as the May 15 withdrawal of British forces from Palestine drew near, David Ben-Gurion organized an offensive to turn the tide and secure the area allotted to the Jewish state as well as the road to Jerusalem. (Paramilitary forces from the Irgun and the Stern Gang, acting independently of Ben-Gurion’s Haganah, attacked the Arab village of Deir Yassin, which overlooked the highway between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and killed about 100 of its inhabitants.

An attack by Arabs four days later killed some 80 Jews, most of them medics, on the way to Rothschild-Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem. When the Haganah, the official force of the Yishuv, took control of Tiberias, Haifa, and Safed —mixed Arab-Jewish towns that fell under the Jewish portion of the partition—the Arabs fled, despite Jewish authorities urging them to stay.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, declared the establishment of the State of Israel. The declaration was made in Tel Aviv, and Ben-Gurion became Israel's first Prime Minister.

The following day, neighbouring Arab states, including Egypt, Jordan (led by British officers), Syria, and Iraq, invaded the newly declared state, marking the beginning of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Despite being outnumbered, the Israeli forces managed to secure their territory and even expand it beyond the UN partition borders.

Interestingly, while the US accorded the new state de facto recognition, Stalin gave it de jure recognition and told the Czech government to ship as much arms as Israel needed, as soon as possible.

The formation of Israel in 1948 was a miracle, the result of decades of political manoeuvring, international diplomacy, and conflict. From the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate to the horrors of the Holocaust a series of historical events and decisions paved the way for the establishment of a Jewish state. The legacy of these events continues to shape the complex and often contentious dynamics of the Middle East today – the subject of the final article in this series.

One major aspect of that legacy is the refugee problem. The UN estimated, probably overestimated, that 650,00 Muslim Arab refugees fled Israel, mostly on orders from their Imams. The Israelis said that the true figure was 500,000. What is often forgotten is that in 1948 there were also hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees in Europe, and 567,654 Jewish refugees from Arab countries, where they had lived for centuries. The total number of Jewish refugees exceeded by a large margin the number of Palestinian refugees. But who now has heard of a Jewish refugee problem? They were quickly settled and became ordinary Israelis.

Yet the Palestinian refugees are still with us, more than ever, still living in squalid camps under the control of brutal terrorists. Arab governments and later the Palestinian organisations have deliberately kept them in camps. As Cairo Radio put it “The refugees are the cornerstone in the Arab struggle against Israel. The refugees are the armaments of the Arabs and Arab nationalism.”