My wife and I recently watched The End of Summer on BBC2. It’s a six-part Scandi-noir story of family relationships over twenty years in Swedish with English sub-titles. I mention it only because the construction of a wind farm featured in it, and one just knew from the outset that something unpleasant was going to be associated with it.

I originally wrote this essay back in January when I was taking frequent looks at the sources of power for the national grid. The early evening is the best time to take a peek. It’s when people are getting home after their day’s toil, putting the kettle and the TV on, settling down at their laptops and PCs and beginning to think about what they’ll be having for supper. Those with EVs will be plugging in at home and those with ‘smart’ electricity meters are perhaps being charged at a premium rate for their power usage.

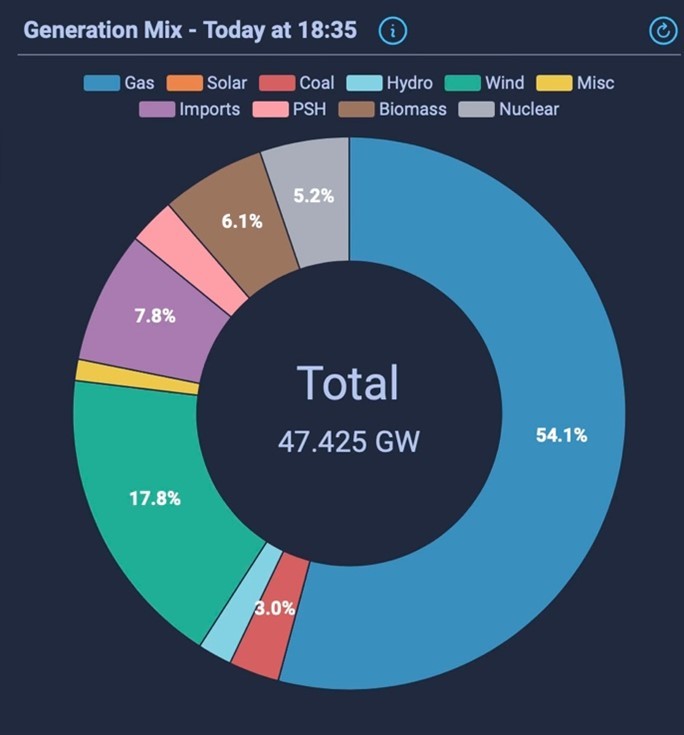

On one January evening, demand on the national grid was approaching its daily peak and a quick check on energydashboard.co.uk showed the demand on the grid at 47.425 gigawatts (GW). Of course, we couldn’t generate all that ourselves so 7.8 GW had to be imported, principally from Norway, France and the Netherlands for which we were paying a premium rate.

We can see on the screenshot from that evening that the heavy lifting was done by gas generation at 54.1% and 3% was being done by coal. It being a reasonable evening for wind in and around the UK, wind power contributed 17.8 % of the requirement. Other notable contributions came from biomass at 6.1% and Nuclear at 5.2%. Biomass generation is a silly process in which Canadian trees are cut down, the wood pelletised and transported across the Atlantic in diesel-powered ships to be burned in the Drax power station in Yorkshire in the belief that this is somehow green and contributing to Net Zero. Hydro-electricity and pumped storage hydro-electricity total 5.3%.

Today we have the planet-brained Ed Milliband in charge at the Department of Energy and Net Zero. Already he has lifted the ban on on-shore wind-farm construction and intends to massively expand offshore windfarms and solar farms. Daniel Zeichner, the Labour MP for the city of Cambridge (a fine rural constituency) has said the Labour party’s policies would -

“Protect the land, support farmers and bring down bills whilst ensuring the agricultural sector achieves net zero. We must also support farmers as they diversify their income streams and make use of land that is not suitable for food production – by enabling them to build renewable energy and plug into the National Grid faster. Under the Conservatives, farmers and landowners have been left waiting years to plug their renewable energy into the grid. No more”.

Let’s get rid of the silly notion once and for all that wind turbines are in any way ‘environmentally friendly’.

The first and obvious thing to say about them is that, wherever they are erected, they offend the eye. Be it onshore, on top of a hill or along a ridgeline, or along the horizon out to sea, no-one can possibly think that they enhance the view. I’m not saying that coal, gas-fired or nuclear power stations are attractive additions to the landscape but at least they are confined to a reasonably compact area. Wind turbines must have a minimum distant between them so that one does not interfere with the wind of another and degrade its efficiency. Standard wind turbines have a rotor diameter of around 300ft and the practice is to site them a minimum of 7 times this distance apart - that’s 700 yards. Thus, a line of ten will cover 6,300 yards - over 3.5 miles and a grid of 12 (3 lines of 4 or 4 of 3) will cover 2,940,000 square yards (607 acres or 246 hectares). That’s quite a chunk of land to you and me.

Out to sea, the Hornsea I wind farm covers 407 square kilometres (40,700 hectares or 100,570 acres). Offshore turbines may be fixed direct to the seabed in a variety of ways depending on the depth of water or they can be semi-floating and tethered. Offshore wind is supposedly set for a massive expansion, and it has already been displacing fishermen. It’s not just the areas of turbines that effects the fishermen but also the uncovered cables on the seabed which bring the power ashore. Betrayed by an incomplete Brexit deal, the UK’s fishing industry is being hampered again through large tracts of sea now being effectively closed to it.

It’s worse onshore, much worse. Here’s a video about wind turbine construction. It has a positive spin, but the images are telling. When a wind turbine is constructed onshore, first a large circular area is excavated, and trenches are dug for the cables. The circular area where the turbine will be erected is given a concrete bed on which the turbine anchorage is placed. A steel network is then constructed about it which is filled with concrete to create a huge ferro-concrete bun-shaped base which will be in the ground forever (lots of CO2 emissions involved there). Once that is done the tower can be constructed, the nacelle and generator raised and fitted, followed by the blades.

When a wind farm is complete and tested and the blades are turning, the power flows. The blades are made of fibreglass and resin layers and are aerodynamically shaped and adjusted for maximum efficiency. Behind the rotor is the nacelle containing the drive shaft, gearbox and generator. The whole assemblage is made to weathercock into the wind automatically. However, the big problem with onshore wind-power is that it is intermittent. In anticyclonic conditions there are windless days when no wind-turbine rotor turns, and no electricity can be generated. Out at sea however, there are far fewer windless days, so generation is more reliable compared to an onshore wind farm. They can generate electricity in winds as light as 7 mph, but the optimum is 18 to 27 mph with the maximum 56 mph. In extreme winds the turbines automatically cut out and ‘feather’ the blades, so they don’t rotate at excessive speed. Occasionally one has failed to do this and burst into flames. Lightning strikes, mechanical failures, lubrication failure and generator overheat are all causes of wind turbine fires which occur much more often than people generally realise.

The life of the average wind turbine is generally from 20 to 25 years after which they must be replaced. Much of the material used in their production can be recycled. Steel, copper and aluminium used can recovered and used again but the blades cannot be. Made from a composite of very fine strands of plastic and glass, which is extremely difficult to process at the point of recycling, they are usually discarded as waste at landfills or incinerated. Although engineers and scientists have found a way to turn fibreglass into a key component used in the production of cement only a small number are used in this way. However, they are also finding ways to repurpose turbine blades as structural elements in their entirety – these include as bike sheds in Denmark, noise barriers for highways in the US, ‘glamping pods’ across festival sites in Europe, or as parts of civil engineering projects, such as pedestrian footbridges in Ireland. Again, those are limited applications and they’re just ‘kicking the can down the road’ as sooner or later these structures in turn will reach the end of their lives.

The impact of turbines on wildlife is a major criticism of them. They are known to kill birds, mostly raptors, and bats in large numbers. The blades create vortices and local areas of low pressure which draw the birds in, and they are struck by the blades. The raptors are attracted to the wind farms because the turbines tend to be sited in the spots that raptors favour - ridges and hills where they find the up-draughts on which to soar. The turbines also seem to create areas where their prey species multiply quickly thus drawing in more raptors to meet an eco-friendly end.

Organisations such as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in Britain bat this off by saying that climate change is a far greater threat to bird species so this little bit of ‘collateral damage’ is a price worth paying to ‘combat climate change’.

As far as bats are concerned, the sudden drops in air pressure around the blades have a disastrous effect on them for two reasons. First, it adversely affects their echo-location ability so they fail to avoid the blades and second, their lungs cannot cope with the pressure changes, so they collapse leading to asphyxiation.

It doesn’t stop at birds and bats. Insects too are affected by wind turbines. Until very recently very little work had been done on this aspect, but it is beginning to attract attention now. German research has shown that a single turbine can cull 40 million insects per year. As of 2022 there were thought to be 70,000 wind turbines in the USA alone, so it is estimated that in the USA 2.8 trillion insects are killed annually by wind turbines. This has been extended to estimate that 13.64 trillion insects are killed annually world-wide by wind turbines. Given how vital insects are in ecosystems whether as pollinators for flora and human crops or as food themselves this could be disastrous for the whole planet. Insects are at the base of the food chain for every other species and the adverse effect wind turbines have on them could create wild-life and agricultural deserts over large areas.

Off-shore turbines don’t get a free pass either. As well as being lethal to sea birds it is thought that the low frequencies set up by the turbines can interfere with the echolocation and communication of whales, dolphins and porpoises leading to navigational confusion and strandings.

Alright, you may say, this is all very well but we need renewable energy to ‘save the planet’ so given what a small area of the Earth is covered by wind turbines isn’t it a piece worth paying? They do, after all, generate energy more cheaply than hydrocarbon fuelled power stations. Well, I hate to pop the balloon here, but they don’t. Wind-power is more expensive than hydrocarbon power.

The first thing to appreciate is that wind power is intermittent. No wind - no power. It therefore needs hydrocarbon-based back up generation and the more turbines there are, the more back-up will be needed. The second thing to understand is that when the turbines are generating, they cannot be turned off. They can’t be controlled in the way that a nuclear, gas or coal-fired power station can be so that the power generated balances the demand. They are generating all the time the wind blows so if there is low demand for the energy (e.g. in the middle of the night) they must be disconnected from the grid. The wind power companies are still paid regardless, and the excess energy produced by them in periods of low demand cannot be stored.

The claim that wind energy would bring domestic power bills tumbling down due to an abundance of cheap offshore wind has been well and truly blown away. In September 2023 the UK’s latest auction for the Contracts for Difference subsidy scheme failed to attract any bidders. The price cap imposed by the UK government of £44 per megawatt/hour (MWh) at 2012 prices (£60 at today’s prices) was simply not viable. This follows on from the decision by Sweden’s Vattenfall to cancel the giant 1.4GW Norfolk Boreas project before construction began.

Ultra-cheap wind power has been ‘just around the corner’ for years. It was supposed to be so cheap it would hugely undercut coal and gas-fired generation and be the cheapest form of energy for the UK. A report in the Guardian claimed that offshore wind power had fallen to £37/MWh. But this all depended on the annual auctions for Contracts for Difference subsidy scheme. The companies were under no obligation to honour these prices and in reality, the wind companies were charging a lot more. In the last auction round this loophole was removed and the wind companies were to be told to honour the contracts. Unsurprisingly, they declined to bid and instead demanded much bigger subsidies.

No evidence has ever been provided that offshore wind energy costs were as low as the auction price indicated. Independent analysts have shown that the real cost is between £80 and £100/MWh and this doesn’t include the system costs of incorporating the intermittent nature of wind power which may be as much as another £50/MWh. Gas-fired power currently sits at around £80/MWh.

It’s not just in the UK that the economic wheels are coming off the wind energy wagon. In the USA developers Shell and Avangrid have pulled out of contracts to build offshore wind farms. In Denmark, the giant wind company Oersted has lost a third of its market value having had to warn investors that it may have to write down its assets in the USA by $2.3 billion. European turbine producers are in trouble after underestimating the costs and challenges of building large turbines for the much more severe conditions encountered by offshore wind farms.

Where does this leave the UK consumer? In contrast to the green lobby’s claims, subsidies for offshore wind are going to add almost £5 billion to the UK’s energy bills this year. The wind industry has been hoist by its own petard. The British government swallowed wholesale its propaganda about falling costs. Thanks to the government’s obsession with renewables (really unreliables) and its destruction of the coal-powered capacity it will probably have to cave into the wind industry’s demand for greater subsidy and hence, higher prices for British households. All of this is in the insane pursuit, let us not forget, of reducing the UK’s CO2 output amounting to 1% of 3% of the 0.04% of the atmosphere which is CO2 to satisfy the Net Zero zealots. It is unmeasurable.

Meanwhile, it is estimated that in the UK we have another 600 years of coal, 50-100 years of shale gas which could be ‘fracked’ and more oil and gas still to be exploited in the North Sea. This would give ample time to construct real alternatives to hydrocarbon-based power generation such as Rolls Royce’s proposed network of small modular nuclear reactors based on its experience with nuclear power plants for naval use. This could also involve the building of molten salt reactors which actually use spent nuclear fuel from first generation nuclear power stations as the fuel. They turn nuclear waste with a half-life of thousands of years into nuclear waste with a half-life of a few hundred years; in doing so they mitigate the nuclear waste problem at the same time as generating power. Energy independence could be beckoning. All it requires is a government to be honest and admit that it got things wrong. The chances of that happening have just been thrown away for the foreseeable future following the recent general election result. It seems unlikely that there will be much change after the next election unless there is a major Reform UK breakthrough which leads to its forming the next government.

And yes, something dark did go on at the wind farm in The End of Summer. It’s still available on BBC iPlayer for at least the next year. I can recommend it.