It’s taken me some time to write this part because the more I looked into matters, the more I found, the more I found the more difficult it became to decide what should be included, what should be left out and where the beginning should be in order to keep this as concise as possible. It also became clear that whereas I had hoped to keep this to just two parts there will have to be more.

We British tend to pride ourselves on not having had a bloody revolution in modern times. Instead, whenever it seemed that matters were getting a bit warm, we’ve achieved political change by evolution, through a series of parliamentary reforms. At least, that is the way the development of parliamentary democracy is presented to us.

People are fond of saying that the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland doesn’t have a written constitution. I don’t think that’s true. We do, but it’s just that it’s not contained in one easy-to-read document. And it is not cast in concrete either; it has been subject to amendment down the centuries as we shall see. Anyone can find this out for themselves. All you need to do is pop onto www.legislation.gov.uk and you can search for whatever you want. It’s all there.

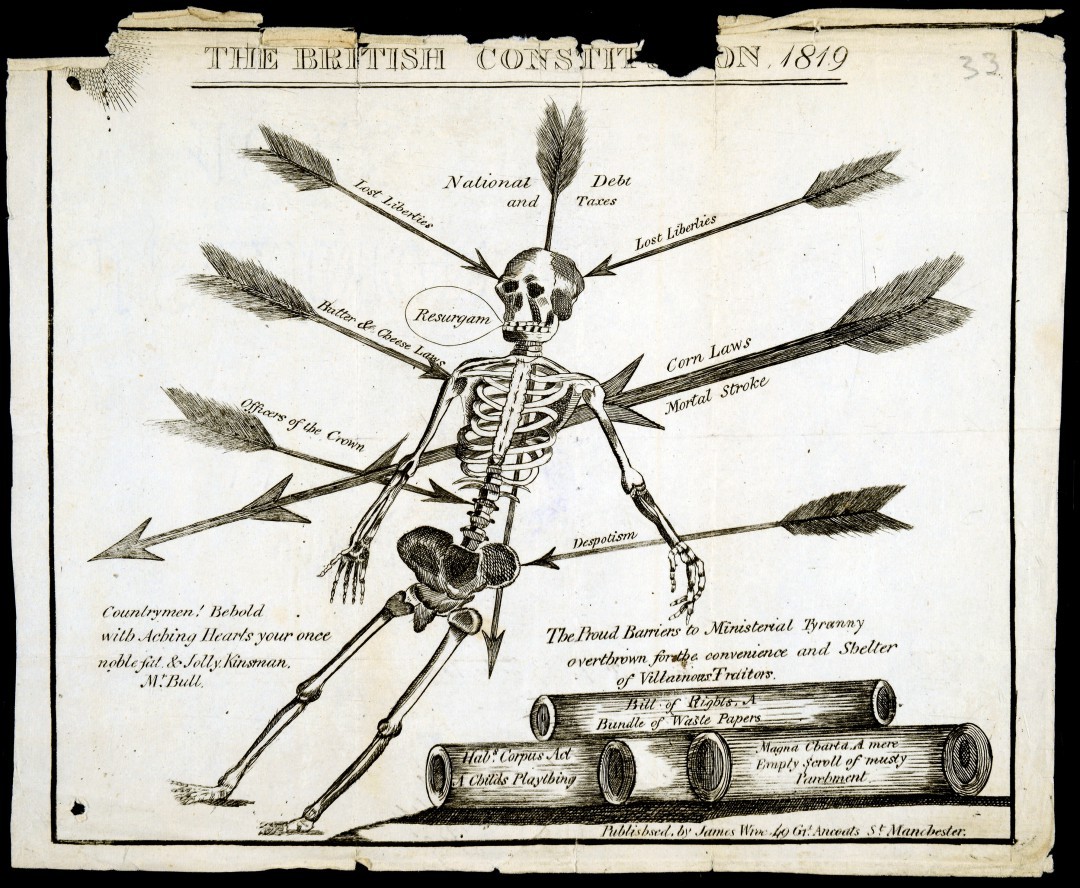

Where to start? Well, Magna Carta obviously and a search for Magna Carta will turn it up. But there’s a problem. It’s Magna Carta 1297, sealed by that well-known champion of the people, Edward I “Longshanks”. This is the version taken into Statute Law. Ever since the barons forced King John to sign in 1215, those who rule have tried to water down its articles. They don’t like it. It is claimed that Magna Carta 1215 was repealed by Pope Innocent III. Whose idea was that? Probably King John’s? Who really knows. The story is that neither side adhered to their commitments and King John was, it is claimed, forced by the Barons to seal the Charter at sword point which contravened Common Law. Why the Pope? Because he was King John’s feudal overlord. Parliament doesn’t have the authority to repeal it since it wasn’t created by Parliament which didn’t exist in 1215. Here’s an article I found which tells the story in an amusing tone.

There were Magna Carta rewrites in 1216-1217, following the First Barons’ War, triggered by Pope Innocent III’s supposed annulment, and again in 1225 before Edwards I’s 1297 version, all trying to get rid of as many of the Barons’ articles as possible, especially Article 61. Much of it has been repealed by subsequent Acts of Parliament because they are outdated or by incorporation into succeeding legislation, so you need to follow all those links too. This is a major point of contention between some campaigners and the British state exemplified by Will Keyte in his campaign at www.commonlawconstitution.org .

There are four copies of Magna Carta 1215 in existence, two at the British Library, one at Lincoln Castle and one at Salisbury Cathedral. Going to Salisbury to examine it is still on my ‘to-do’ list. However, there’s no need if you look it up on Encyclopedia.com. There’s a modern rendering of Magna Carta here but it looks as though it’s the 1216-17 version.

There is also the lesser-known but no less important Charter of the Forest which was almost certainly infringed during the enclosures, a great Act of Theft committed against the people.

Let’s leave that argument aside and take the remains of the 1297 version of Magna Carta which is on the Statute Book. Article 29 says:

NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor [X1condemn him,] but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.

Two phrases hit you in the face: ‘By lawful judgement of his Peers’ and the ‘Law of the Land’.

The first one is easy as far as the Barons were concerned: Barons shall be judged by Barons and Freemen should be judged by Freemen. But what of the serfs? Surely serfs would be judged by serfs, would they not? What defines a Freeman these days anyway? Whatever the interpretation it is surely what gives us the right to a trial by jury (not a jury trial) of our peers whomsoever they may be. Of course, that could present a problem depending on where the trial was to take place and therefore the ethnic, religious and political make-up of a jury.

‘The Law of the Land’ is the really interesting phrase. What does it mean? It has come to mean the body of legislation that has been created as well as the Common Law on which it is supposed to be based. At the time of Magna Carta it can only have meant one thing and that is the Common Law and the ancient customs of the people lost in the mists of time - Lex Angliae non scripta – the unwritten laws of the England. That is most important. It derived its authority from immemorial usage and "universal reception throughout the kingdom," as phrased by Sir William Blackstone (1723–1780) in his Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1769). The common law was contrasted with the written statutory laws enacted by Parliament.

Claims are made that Common Law incorporates Natural Law which is a law of rule or action which is implicit in the very nature of things and is therefore immutable. It includes too biblical laws, God’s law, as laid down in the Ten Commandments according to the analysis of St Thomas Aquinas. You can read about the development of Natural Law here if you wish. It’s quite long.

By now we can see that the claim that King John’s signing of Magna Carta under duress contravened Common Law is a tacit admission that there is a Higher Law than anything produced by the hand of man.

Although Article 61 (Chapter 61) was supposed to have been removed from Magna Carta, the last time Barons invoked it was in 2001. Four of them, The Duke of Rutland, Viscount Masserene and Ferrard, Lord Hamilton of Dalzell and Lord Ashbourne, petitioned the Queen about the Treaty of Nice. They got nowhere but it added to the pressure for a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union.

Suffice it to say that The-Powers-that-Be have, down the centuries, hidden from us the truth about our constitution which is based on Common Law. If you speak to a lawyer, they will tell you that Common Law is the body of decisions made by judges known as Stare Decisis, the precedents on which judgements will rely. This is what the legal profession thinks is Common Law. Well, it would, wouldn’t it, because it benefits them. Stare Decisis and statutes are the whole basis of their money-making and their hold over us.

Judges’ decisions are, of course, said to have been made based on Common Law but there is an elephant in the room, to use that now hackneyed expression. Who pays the judges? Why, It’s the State. Is it likely, therefore, that the judges will make any decisions except in the most trivial cases, which run against the interests of the State? I don’t think so.

Common Law has been removed from the syllabi of Law Schools since about 1970 but there are still plenty of lawyers who do know about it and understand it.

Scotland is different because Scots Law is based on Roman Law. This essential difference could be the reason why many Scots were happier to be in the EU than the majority of the English and Welsh. Essentially, in England anything is permissible unless it is specifically forbidden whereas in Scotland it is not permissible unless permission is granted by higher authority. Very Roman, very Napoleonic. Many enlightened Scots (such as me), however, have come to prefer the English arrangement.

There we should leave Magna Carta and Common Law and fast-forward to the end of the 17th Century. The year 1688 in British history is marked as the year of the Glorious Revolution, when the idea of a Constitutional Monarchy was established. It was following the accession of William III & II and Mary II that the foundations of the modern British state, and much else, were laid. Just how glorious was it, and for whom?

As much as some people (a growing number?) would like to be able to use real Common Law courts we can’t. We would almost certainly be scoffed at and far too few people are aware of the principles and the Common Law responsibilities involved. Therefore, we need to understand the nature of the system we do live in so that we can, if need be and if possible, use it against the system itself. To do this we should understand the Primary Legislation which set up our current system of government and which has underpinned the British State ever since.

The first thing to look at is the Act of Wil. & Mar. (1688) which swept away all previous arrangements and established the legitimacy of the two Houses of Parliament. It created a new government and a new legal system, giving legitimacy to what followed. This legislation, with amendments, is currently still in force.

The next, and much fêted, Act of William and Mary is the Bill of Rights (1688). It starts by listing the offences which occurred under the rule of James II and then removes them. Here we read that, under Subjects Rights in this Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Subject and Settling the Succession of the Crown, inter alia:

The King or Queen cannot suspend, dispense with or execute laws without the consent of Parliament.

Ecclesiastical courts are illegal.

The King or Queen cannot raise an army without the consent of Parliament.

The King or Queen cannot levy taxes without the consent of Parliament.

Subjects have the right to petition the King or Queen without fear of prosecution or imprisonment.

Protestants may bear arms for their defence as allowed by law. (That’s a good one. What happened?).

That freedom of speech and debates in Parliament cannot be impeached or questioned outside Parliament.

The election of members of Parliament must be free.

We should now take a look at the Coronation Oath Act which specifies The Oath which must be taken by the King or Queen before giving Royal Assent to any legislation. It starts by declaring the doubts about earlier forms of Regnal Oath and goes on to specify the wording of The Oath and that every succeeding King or Queen shall swear it. We can see here that there is an acknowledged difference between Statutes and Law and Customs. That puts the King or Queen in a bit of a bind. What should he or she do if an Act of Parliament runs counter to the Laws and Customs of the people, as many do? For example, anything to do with the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union, which almost by definition gives away sovereignty which is not Parliament’s to give away in the first place? Remember all that political guff about the UK not giving away sovereignty but rather ‘pooling’ it? Pooling it, at the very least, waters it down.

Next is the Act of Settlement 1700. Although primarily concerned with who will succeed William III, Queen Mary II being deceased, there is a very important bit down at the bottom in Provision IV – the Laws and Statutes of the Realm Confirmed. Under this we see that the laws of England are the Birthright of The People and all Kings and Queens and all Ministers should serve them according to the same (i.e. the said Laws and Statutes).

Now it’s appropriate to take a look at the Great Seal Act and the Treason Act. The Great Seal referred to was the Great Seal of England which has with Union become the Great Seal of the Realm. It is used to signify the Sovereign’s approval of State documents, and the original Act charges that the Lord Chancellor or commissioners appointed should be the keeper (s). Thus, the Lord Chancellor or the Commissioners must ensure that the Great Seal is attached to All Acts of Parliament after Royal Assent is given. We see that at the top of the Act of Settlement 1700 for example, where it says Act in Force at Royal Assent. Have they always done so? It’s a good question. If not, is the Act or Statute even legal?

It's interesting here to find out when the last time was that an Act received the Royal Assent of the Monarch in person in Parliament. A quick search reveals this to be 12th August 1854! The power was actually delegated to Lords Commissioners by the Royal Assent by Commission Act of 1541 which authorised the execution of Queen Katharine Howard and spared Henry VIII’s feelings by having Commissioners do it in Parliament for him. This was repealed and replaced by the Royal Assent Act 1967.

The first few lines of the Treason Act should give all politicians pause for thought.

Whereas nothing is more just and reasonable than that Persons prosecuted for High Treason and Misprision of Treason whereby the Liberties Lives Honour Estates Bloud and Posterity of the Subjects may bee lost and destroyed should bee justly and equally tried …..

So, depriving any subject of liberty, life, honour, estate, blood and a future is considered High Treason. But Provision V states that the offender has to be indicted by Grand Jury within three years of the treason or offence.

If you’ve been looking at the links to www.legislation.gov.uk you’ll have noticed that on each page there is a choice of version - Latest Available or Original (as Enacted). But Original is greyed out. Originals of these Acts of Parliament which defined the Government of Britain in 1688 and after are not available. As the Acts have been amended in many instances it led me to wonder why. What is it that we are not supposed to find out?

Fortunately some good folk have been on the case as I found out with the Act of Settlement (1700) when I came across this. If we look at the original Provision III, Further Provisions for Securing the Religion, Laws and Liberties of These Realms we find this:

That no person who has an office or place of profit under the King, or receives a pension from the Crown, shall be capable of serving as a member of the House of Commons;

That after the said limitation shall take effect as aforesaid, judges commissions be made quamdiu se bene gesserint, and their salaries ascertained and established; but upon the address of both Houses of Parliament it may be lawful to remove them;

Quamdiu se bene gesserint means for as long as they have conducted themselves well.

Does that not suggest that no Minister of the Crown, no member of the judiciary, in receipt of a Crown salary or other preferment can sit in Parliament in the House of Commons? The implications of that for the way Parliament is currently constituted and conducts its business are huge – no member of the executive or the judiciary can sit in the Commons. How can the business of the House of Commons be controlled if the executive is not in it, one might ask? Therefore, it has been removed. When and by whom? Clicking on links reveals that the words were repealed by the Statute Law Revision and Civil Procedure Act 1881 (under the second Gladstone Liberal ministry) but “no web publishable format is available”.

One could get bogged down for hours, days or weeks even, in trying to trace the amendments and repeals to primary legislation but, in the interests of getting this article finished I’ll leave it there! You get the picture.

If you’re still with me so far, well done – especially if you’ve read all the links. In the next part(s) I aim to describe how Parliament was taken over by the political parties, how they in turn have been controlled and corrupted by money and corporate interests and finally what, if anything, we can do about it.