On the 21st of October 1805 the British fleet, under Horatio Nelson, met the combined French and Spanish fleets under French Admiral Villeneuve, for one of the most famous naval battles in history, off Cape Trafalgar, Spain. The outcome was a decisive victory for the British, that ensured that Britain would not be invaded by Bonaparte’s all-conquering French army and, ultimately, that he would not achieve hegemony over Europe or extend his Empire to India and North America.

Four years earlier, Admiral John Jervis, Earl St Vincent had quipped to the Board of the Admiralty, “I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come. I say only they will not come by sea.” But by 1805, that was far from certain. Knowing that he had to defeat Britain to achieve his goal of world domination, Bonaparte had decided on two strategies: economic war against Britain’s trade and finance and then invasion.

The economic war was a failure, but the threat of invasion was the greatest threat Britain faced between the Spanish Armada in 1588 and Hitler’s threat in 1940. To achieve his goal, Boney had built a formidable navy of his own, which together with the Spanish fleet, also under French control, was much bigger and in better condition than the sea-worn Royal Navy. Napoleon wanted the fight, he had the ships, and he had the money, but as we shall see, he did not have the men to compare with the superb men of the Royal Navy who, in 1805, alone stood between Bonaparte, the invasion of England and world domination.

Britain had been at war with France since 1793 when the revolutionaries lopped of Louis XVI head, except for a very uneasy truce between 1801 and 1803 that both sides knew could not hold.

An interesting aside is the defeat of a French Army in 1803 in Haiti, in revolt against French rule, aided by a British naval blockade. This led Boney to give up his dream of a North American Empire and agree to the sale a vast area of what is now the USA, west of the Mississippi River and stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, to the US government, a transaction known as the Louisiana Purchase –financed by British banks.

The foundation for the British victory at Trafalgar lay years in the past, initially with those ‘nurseries of seamen’, the merchant marine, the fishing fleet, especially the whalers and the Newfoundland fisheries, and the North Sea coal trade between Northeast England and the Thames. Built on this was the Royal Navy’s close blockade of the Atlantic coast, from the Channel to Gibraltar which, with all the weather patterns against them, demanded superb organisation, iron discipline and a huge amount of nerve in what was almost certainly the greatest act of seamanship that ever was or ever will be – and it went on for years.

The weak were weeded out very quickly, but the best thrived and became the very masters of their trade. As another hero of Trafalgar, second-in-command Cuthbert Collingwood, said, it caused them to ‘rub out can’t and put in try’. ‘Cuddy’ had commanded the blockade in the 1790s and said that it was ‘more dangerous than a battle once a week’. It certainly amazed the French who, in all but the most extreme weather, would see the weather-beaten British ships patrolling their coast day after day, adding greatly to the French Navy’s sense of inferiority.

The blockade, designed to keep the French Navy in port, also had the effect of preventing French and Spanish crews gaining experience and eliminating their seaborne trade, at huge cost to their economies.

Another key factor in the Royal Navy’s efficiency was that its officers had to pass a difficult oral test after demonstrating skill at sea to become a lieutenant. Men were even promoted from the lower deck; ten per cent of the lieutenants at Trafalgar had been promoted this way.

Other important factors in the British victory were intelligent direction from the Admiralty coupled with the superb skill of frigate captains like Richard Keats in shadowing the Franco-Spanish fleet and keeping them informed, superior battle tactics and, above all, superior guns and gunnery as described below.

And of course, we must not forget the men in charge, Horatio Nelson and Cuthbert ‘Cuddy’ Collingwood, close friends and each the other’s greatest admirer. The superlative Nelson is well-known and is well and charmingly described in Anna’s companion article. Suffice to say here that he was, more than anything else, a great leader of men, loved by those who served under him. I think the following gives a good measure of the man, written by a seaman who served under him in Victory, a few months before Trafalgar about a dangerous fire on board:

“Once the Victory took fire near the Powder Magazine. The whole of the terrified crew runned up the riggin and at that dreadful moment, when every Man thought it his last hour, Lord Nelson was then as cool and composed as ever I saw him before. He orders every man below to put out the fire, and such is the confidence and respect that the sailors have for him that everyone obied him and in twenty Minutes the fire was got under. Thus from the Admiral’s fortitude and the readiness his Orders were Obeid, was the Victory saved and All Souls on board.”

Cuthbert Collingwood is largely now forgotten. A better seaman than Nelson, equally loved by his men, but nowhere near as charismatic. He stands now guarding the mouth of the Tyne and as a statue in Newcastle. He genuinely deserves an article of his own, and the book ‘Admiral Collingwood – Nelson’s Own Hero’ is highly recommended.

We need not trouble too much about the manoeuvrings that preceded Trafalgar. 1805 had started with the Combined Franco-Spanish fleet blockaded in Brest, Ferrol, Cadiz, and Toulon. Napoleon, under the illusion that he could manoeuvre fleets under sail like armies on land, had concocted a plan for them to link up and take control of the Channel, allowing his Armée d'Angleterre in Boulogne to invade.

The game started in March 1805 when Villeneuve escaped from Toulon. Nelson was also in the Mediterranean and soon gave chase, right across to the West Indies and back to Ferrol in northern Spain. With Villeneuve safely bottled up, Nelson took the opportunity of returning to England and discuss strategy with the government, leaving Collingwood in charge, arriving off the Isle of Wight on 17 August 1805.

While ‘dallying’ with Lady Hamilton, Nelson learned that Villeneuve was out of Ferrol and had gone to Cadiz, where Collingwood had adroitly stood aside to let him enter before blockading him in that port again. Nelson was ordered to sea and left Portsmouth on 14 September, never to see England again. As he left Portsmouth many hundreds of people gathered to see him off, pressing close “touching his coat, kneeling, praying, crying and cheering”, written up later as ‘the redeemer’s entry into Jerusalem’.

Nelson had decided on enticing Villeneuve out to sea for a battle of annihilation to end the threat of invasion once and for all. Nelson therefore positioned his fleet about 35 miles west of Cadiz, where he could let the enemy out while being ideally placed to intercept a French fleet from Best. Nelson was confident that Villeneuve would put to sea, so spent time with his Captains explaining to them the ‘Nelson Touch’ a new(ish) doctrine of cutting the enemy line of battle and getting as close as possible to enemy ships, saying that in case his signals could not be seen “no Captain can do very wrong if he places his Ship alongside that of an Enemy.”

The Combined Fleet left Cadiz on 19 October, spotted immediately by Nelson’s watching frigates. The British fleet saw them at daylight, 21 October 1805. A seaman in Victory later wrote “On Monday the 21st at day light the French and Spanish Fleets Was like a great wood on our lee bow which cheered the hearts of every british tar in the Victory like lions Anxious to be at it.”

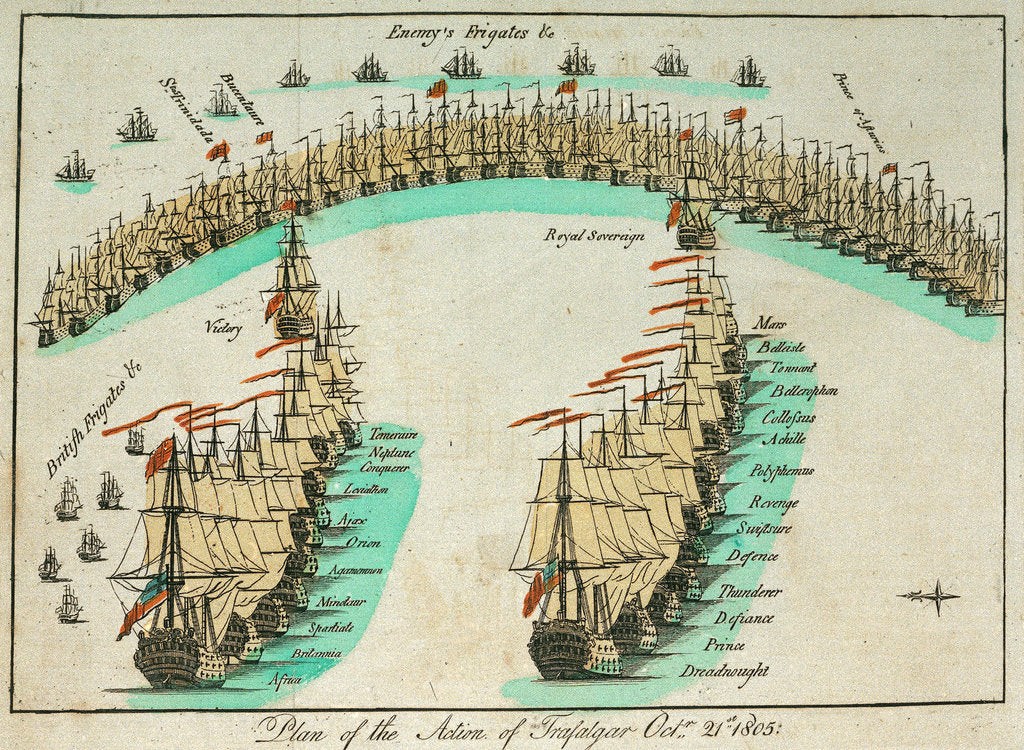

Nelson’s twenty-seven ships, approximately 17,000 men and 2,148 guns faced Villeneuve’s thirty-three ships, some 30,000 seamen and soldiers and 2,632 guns. The British, as planned, divided into two columns hoping to cut the French line and engage the enemy at close quarters. The two fleets approached each other at an agonisingly slow one and a half knots (about 1.7 mph). At 11.50 Nelson hoisted his famous message “England expects that every man will do his duty’. Six minutes later the French opened fire on Collingwood’s ship, leading one of the divisions. At the same time Villeneuve hoisted his flag in Bucentaure in the centre of the Combined Fleet line. Nelson altered course to head straight for it. As the two British divisions were approaching the Combined Fleet nearly perpendicularly, they could not bring their guns to bear on the enemy, whereas the French and Spanish ships could fire a full broadside at the British ships, which came on in silence, preserving ammunition and the energy of the gun crews. Many British ships, including Victory, suffered their worst casualties during this, opening, stage of the battle.

The British opened fire at 12.05 when Collingwood’s “Royal Sovereign most nobly began to fire and passed through the Enemy’s line under the stern of the Santa Anna.” At nearly half past noon Victory passed directly astern of the Bucentaure, almost close enough for the British gunners to reach out and grab her flag, when Bosun William Willmet fired the Victory's massive 68-pounder port forecastle carronade, loaded with a roundshot and 500 musket balls sweeping away most of Bucentaure's stem. Both divisions of the British fleet were now engaged.

The Battle of Trafalgar had begun.

To describe the battle in detail is very difficult, so instead I suggest that you watch this short, animated video, which covers the major details. Watch this very good French animated documentary for a longer more detailed picture of the battle.

When the battle was over 17 of the 33 French and Spanish ships of the line were in British hands and another had blown up. Several of the badly battered Franco-Spanish ships that had escaped toward Cadiz subsequently sank. The British lost 441 killed in the battle compared with nearly 2,500 French and Spanish battle deaths. Moreover, during the almost five hours of fighting not a single British ship was sunk or forced to strike its colours. Given the disadvantages of ships, men and guns under which the British fought, how can this decisive victory be explained?

The Combined Fleet had more, larger, and often better-constructed ships. It also had considerably more and heavier guns than the British. If calculations of potential firepower were all that mattered, the French and Spanish must surely have had the better of it.

Battles like Trafalgar are not won by admirals or captains once the firing begins. Once they have done their part and put their ships in contact with the enemy, the decision lies in the hands of the sailors who handle the guns. Under Nelson these men thought themselves invincible. Bravery was the single-most common characteristic among the officers of Nelson's fleet, and it was present in equal measure among his crews. Once a ship was engaged, Captains had little to do except pace the quarterdeck under fire, so as to inspire the crew.

Apart from discipline, confidence and courage, the final major element of British success was gunnery. A crucial difference between the two fleets was doctrinal. British captains trained their gun crews to fire rapidly and not to worry much about accuracy as they fired at close range and impossible to miss the target. French crews were trained to take careful aim and fire slowly, as befits a navy that made it a practice to fight from a distance and retreat to safety whenever possible.

It was also French policy to aim for masts and rigging in order to hamper the enemy's sailing ability. British doctrine, on the other hand, called for aiming at the hull of enemy ships to cause as much death and destruction as possible. One French captain complained after the battle, "An English shot would kill twenty of our men; a French shot in return would cut a hole in a sail."

Moreover, British gun crews loaded and fired much faster than their French or Spanish counterparts. According to studies of rates of fire from other engagements, Franco-Spanish gunners could fire on average one shot every six minutes. British gun crews were markedly superior. The ships of Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood's lee column, for instance, fired their first three broadsides in just over three minutes, with a sustained rate of fire of one round every two minutes.

Assuming a pair of British and French 100-gun ships were exchanging broadsides, at any given moment 50 guns are engaged on each ship. In a ten-minute battle the French would get off two broadsides. The British would get off six. Over the next hour, the French would be lucky to get off ten more broadsides while the British would deliver 30. During the first ten minutes, the French ship could expect to absorb 300 rounds into its hull, while the British would only have to endure 100 rounds, and most of those would pass through sails and rigging.

Because the British habitually double-and triple-shotted their guns, the French ship would actually be struck by 600 to 900 rounds. Also, British rounds were killing men and wrecking guns, assuring that each successive French broadside would be weaker than the previous.

At Trafalgar, the carnage inflicted by the terrible broadsides of a British ship was more than often enough to decide a duel. Writing after the battle, the acting captain of Bellerophon, told of the engagement with the French Aigle: "Our fire was so hot that we soon drove them from the lower decks, after which our people … elevated their guns, so as to tear their decks and sides to pieces. When she got clear of us and did not return a single shot while we raked her; her starboard side was entirely beaten in." The Aigle lost more than two-thirds of her crew killed and wounded and captured.

This was a story repeated in many particulars throughout the engagement. For instance, when the Royal Sovereign faced eight enemy ships she inflicted double her own losses on the massive Spanish ship the Santa Ana and punished most of the other seven vessels equally hard. The Colossus, which engaged in a long fight against three enemy ships and suffered the highest number of British losses that day (40 killed, 160 wounded), still managed to inflict almost three times as many casualties on the enemy.

In a single afternoon the Royal Navy put a definitive end to any hope Napoleon had to invade England and assured Great Britain's naval supremacy for the next century.

Nelson had remained on deck, in full uniform, and so when the Redoubtable came alongside the Victory he was easy to spot, and was shot through his left shoulder, rupturing the pulmonary artery and travelling to his spine. Nelson knew he was dying and even told Hardy ‘They have done for me at last, my backbone is shot through ‘.

The Temeraire soon came alongside the Redoubtable and the French described her broadside as ‘murderous’. In under half an hour the Redoubtable was almost entirely destroyed and out of 634 men, 300 were killed and 222 wounded, including nearly all her officers.

Meanwhile, onboard the Victory, Nelson knew he didn’t have long to live and asked Hardy how the battle was going. Hardy informed Nelson of his victory, and Nelson asked Hardy not to throw him overboard when he died. He passed away at approximately 4pm, by which time a victory was certain.

The next day, Collinwood opened his wonderful General Order of thanks to the officers and men of the fleet with this tribute: The ever to be lamented death of …Admiral Lord .. Nelson .. the Commander in Chief, who fell in the action of the 21st. in the arms of victory, covered with glory, whose memory will be ever dear to the British Navy and the British Nation, whose zeal for the honour of his King, and for the interests of his country, will ever be held up as a shining example for a British seaman.”

In England, news of the victory at Trafalgar set off jubilation and general rejoicing, which was almost immediately subdued by the announcement of Lord Nelson's death. To the country, his life seemed a particularly heavy price to pay even for so great a triumph. Nelson, though, had seemed to know that this battle would be his last and told many of his captains that they would not see him alive again. He died knowing he had won a great victory and not a single British ship had struck. It was how he most wanted to go. And he had his desire in annihilating the Franco-Spanish fleet.

But this tale does not end quite yet, for in the direct aftermath of the battle, the exhausted men of the British fleet in their battered ships, faced yet another, even more formidable enemy – the Atlantic Ocean at her worst. What followed leaves this writer speechless in admiration for those heroic men.

By 0800, 22 October the survivors of the battle were struck by an unusually ferocious storm, estimated at force ten, even eleven – near hurricane force. The storm lasted for a pitiless seven days. Amazing, but anonymous feats of seamanship kept every British ship safe, and the big-hearted British seamen rescued many a French and Spanish sailor, the crew of the Naiad frigate, for example, rowed through mountainous seas to rescue 190 men and one woman of the French L’Achille.

It's a well-worn phrase, but never so true of the men of the Royal Navy of that era: we shall never see their like again. But we can, and should, be immensely proud of them.

Click on the continue button below for Anna's excellent depiction of the immortal Nelson.