The wilder part of the internet and MSM are alight with claims that container ship DALI deliberately rammed Baltimore's Francis Scott Key Bridge. The CIA did it they say. Or China, whose hackers took remote control of the ship. Or the Israelis taking revenge for US betrayal.

The Guardian sees it differently. Their conspiracy is one of far-right racists using the accident to blame wokery and substandard third world crews. Obviously, no one with a sliver of sagacity gives credence to the Guardian, so let’s just look at what happened. But before we do, as this is not a thriller, let me state that this was an accident and nothing else.

Early on 26th March, DALI, outbound for Sri Lanka with two port authority pilots on board, hit one of the bridge’s supports causing it to collapse into the Patapsco River. Six men working on the bridge, an El Salvadorian, two Mexicans, a Honduran and two Guatemalans were killed.

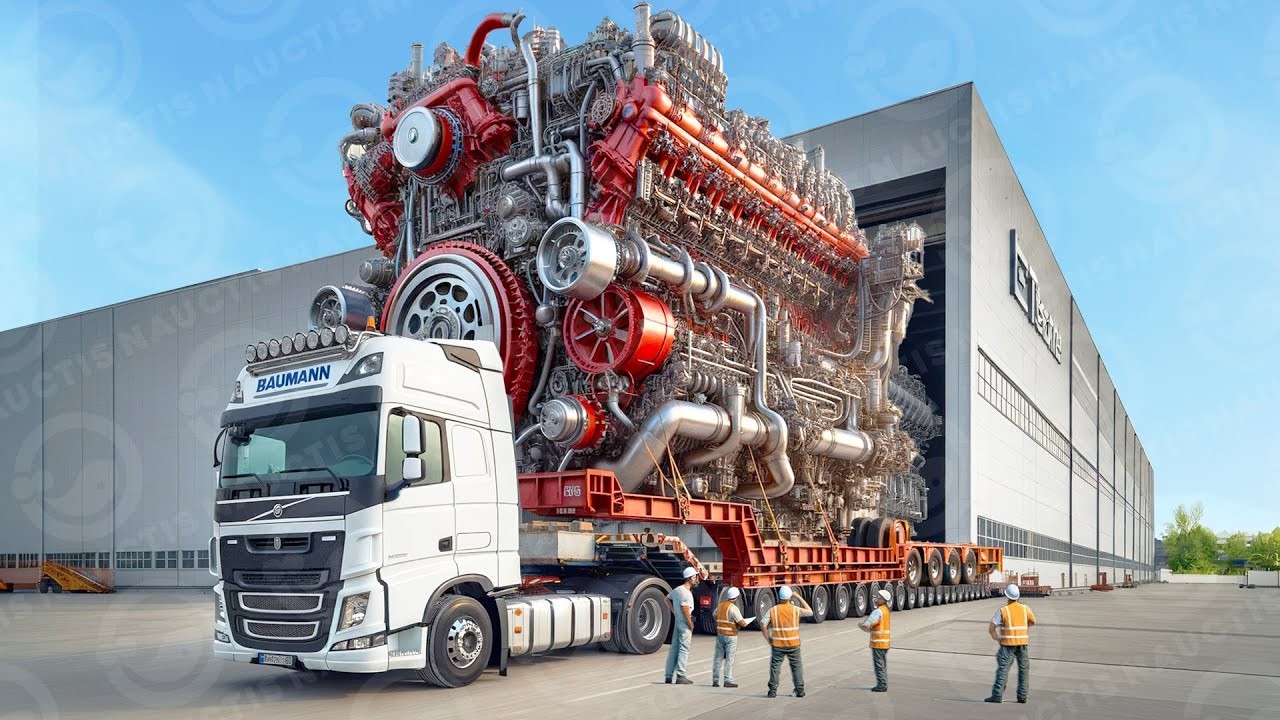

DALI, a medium sized container ship of 10,000 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units: a cargo carrying capacity expressed in terms of how many twenty-foot containers can be carried), has a deadweight (the weight of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, provisions and crew she can carry), of 116,851 tonnes, is 300m long and 48m wide.

Built in Korea in 2015, she is ‘classed’ by the respected Japanese society ClassNK. Classification societies set technical standards for building quality, maintenance and technical management and conduct regular inspections, with an exhaustive, in-depth inspection one every five years.

DALI is registered in Singapore, one of the better flag state authorities, and must meet Singapore flag standards. The Singapore Registry of Ships also does inspections, often contracting them to one of the major societies such as ClassNK or Lloyds Register of Shipping.

The ship is owned by a Singapore company, possibly investors knowing nothing about ships or shipping and daily technical and crew management is contracted to Synergy Marine Group (SMG) an Indian-owned company. DALI is manned by Indian nationals.

As a generalisation Indian management and crew have a reputation for excellent paperwork, but less than excellent engineering and navigational ability. However, the best Indian crews are as good as most. SMG is big, with 24,000 seafarers on its books and almost 700 ships under management.

So, what caused DALI to collide with the bridge? Available facts are few, but just after midnight she left her berth assisted by two tugs. By 01.07 local time she was in the channel leading in and out of Baltimore harbour. The tugs had left, on their way to another job. All entirely normal.

Between 01.23:33 and 23:59 there were several alarms and DALI blacked out - a total loss of electric power - doing about 8.5 knots (10.2 mph). Power was restored at 01.25:31, and steering commands were given. A second blackout occurred at 01.26:37 and a pilot asked for tug assistance. At 01.27:04 the crew dropped the port anchor to try to stop the ship and turn her to port, away from the bridge support. Electric power was again restored at 01.27:11 and thick black smoke was seen belching from the ship’s funnel. At 01.27.27 the pilot told the port authority that the ship had lost all power and advised them to close the bridge. As there were workmen on the bridge there were police at both ends, who closed it immediately.

DALI hit the bridge support on her starboard side at 01.28:45, about five minutes after first losing power. (Times are as reported by the United States Coast Guard [USCG] who took them from the ship’s voyage data recorder [VDR] - like an aircraft’s black box but less sophisticated).

No other details have been released, so what follows is necessarily speculative. But as I am a fully qualified marine engineer with twenty years’ sea service and over thirty years’ experience in ship management and marine casualty investigation, it is informed speculation.

Ocean-going ship’s critical equipment have two or three layers of redundancy. Blackouts are not common, but do occur, and for a myriad of reasons. Ships therefore have an emergency generator (EG), which should start automatically and supply power within 45 seconds to emergency lighting, radios, the VDR and, critically, the steering gear, the hydraulic equipment that turns the rudder. DALI first blacked out at 01.23:33 so the steering gear should have been working by 01.24:09 at the latest. The ship was moving at over 8 knots so there was enough forward momentum for the rudder to work. The second blackout lasted forty-three seconds. Regulations stipulate a maximum of 45 seconds but most EGs supply power within 15-20 seconds.

A major question is, therefore, did the emergency generator start and supply power to the steering gear? If it did, what stopped the crew from keeping DALI in the channel and away from the bridge? Did the EG start, did it supply power to the steering? If not, why not?

There are questions about the entire electrical supply plant. DALI has four main electrical generators each capable of carrying normal sea load. It is normal practice to run at least two of them when manoeuvring in and out of port, just in case. The other two should be set up to start automatically in the event of a problem or a sudden increase in electric load. The system is protected by a series of preferential trips. If an overload occurs, supply to non-essential equipment like the galley or air-conditioning trips off. Whether or not these systems worked properly is especially important in terms of liability. There is talk of DALI having electrical problems before she sailed, with the shippers who loaded refrigerated containers alleging that they had to supply them with their own generator as the ship’s electrical supply was unreliable.

Loss of electric power means loss of propulsive power. The 55,630hp (41,000kW) main engine coupled to the propeller has large electrically driven lube oil and cooling water pumps as well as, in modern engines, computer-controlled functions like fuel injection timing. The EG does not supply enough power for these, so the main engine shuts down.

Crew response will come under scrutiny. Did they (and the pilot) act with a reasonable degree of competence? Did they do anything that might have contributed to DALI striking the bridge? When I was at sea it was standard practice to have three engineers in the engine room on standby for harbour passages. That remains best practice, but it is possible that there was nobody in the engine room at all, as the main engine can be started and stopped from the bridge - the ship’s navigation bridge that is.

Much has been made of the thick plume of black smoke from the funnel after main power was restored. This was probably the crew starting the main engine, most likely astern. The smoke is caused by turbocharger lag. It takes time for a turbocharger to get up to speed and, until it does, there insufficient air for clean combustion. This is entirely normal. Such engines can burn well over a litre of fuel a second and need large volumes of air to burn it completely.

Radar tracking of DALI’s course show her veering slightly to starboard and out of the channel shortly after the blackout, suggesting that there was no power to the steering. Some have said the bow thrusters should have been used for steering. This is not correct. Even if there was full power to the electrically driven thrusters, they are ineffective when moving at over three knots. DALI was making between 8.5 and 7.6 knots.

Most ship’s propellers rotate clockwise going ahead, giving a slight tendency to turn the ship to port. Rotating anticlockwise going astern the tendency is to starboard (towards the bridge support). If a crash astern order is given with the ship moving ahead the propeller ‘slips’ and initially does no useful work. It might therefore have been better to start the engine slow ahead and, if they had power to the steering, put the rudder hard over to port and turn away from the bridge. Wind, current and tide however, probably had more effect in pushing DALI to starboard.

All of this is important to determine liability and who pays what. Maritime law and insurance are complex. Lengthy litigation is a certainty. Following any major marine casualty there is a scramble by the parties involved; the ship’s P&I Club, cargo insurers and the charterers’ (Maersk Line) liability underwriters, to avoid or minimise liability.

Which one is liable depends on several factors dependent on proximate cause – the act, intentional or negligent, found to have caused the casualty. This and other factors will decide which insurers pays for the salvage, damage to the ship and her cargo. The ship owner contracts to provide a ship that is seaworthy at the commencement of the voyage ie, departure from the berth at Baltimore. If cargo interests and charterers prove that the defect that caused the collision existed before departure they are off the hook. If not, cargo will share the costs. If it is found that the problem was caused by an inherent vice in the fuel supplied by the Charterer, his liability insurance will pay.

It has been said that the casualty was caused by pilot error and therefore the fault of the port authority. This is incorrect. Pilot error might have caused or contributed to the casualty, but neither he nor the port authority will attract liability. Legally, a ship is always under the command and control of her Captain. When manoeuvring in and out of port the pilot is in effective control and gives orders to control the ship’s speed and course. But he is an advisor with no legal authority.

Ships have numerous insurances, chiefly hull and machinery (H&M) and protection and indemnity (P&I) covering the ship itself and third-party liability, respectively. P&I cover for DALI is provided by London-based mutual Britannia P&I Club, founded in 1855 and highly professional.

In the first instance Britannia will be liable for claims against the ship. The Club is a member of the International Group (IG), an association of the twelve leading P&I Clubs, providing liability cover for 90% of the world's ocean-going tonnage. The group provides layers of cover up to about $3 billion. Expect the US authorities to target this amount. IG has its own re-insurance, much on London’s Lloyds’ market.

Most legal maritime disputes are held in London, under English law and jurisdiction. A hearing may be held the High Court or under the London Maritime Arbitrators Association. Either way it will be a lawyer’s wet dream, lengthy and expensive.

London litigation will, however, be relatively civilised. In the US it is likely to be a bit livelier. The bridge’s insurers will look to recover their losses. The port will sue for loss of revenue, as will ships stuck in or outside of the port. Those awaiting delayed cargo will sue. And so on, joined in by Uncle Tom Cobley and all who, by the exercise of some imagination, think that they might have been adversely affected.

The marine insurers might try to limit liability under the UN’s Convention on Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims. This would limit liability to the salved value of DALI and her cargo, at a guess anything between $50 million and $100 million. I am not sure if the US has ratified the convention and anyhow, but if it has it is not above applying political pressure to squeeze the maximum out of foreign insurers (see World Trade Centre and Deepwater Horizon claims), especially in an election year.

Whether a ship owner can limit liability depends on the cause of the casualty and if he should have done something to stop it. If rumours of electrical problems before sailing are correct, and if they are related to the blackout, it will be argued that a reasonably diligent owner should have known about it and prevented departure until the problem was resolved properly. If the defect was of a magnitude that it should have been reported to the port authority or the classification society but was not, it is not only likely that the owner will be found liable, but also possible that criminal proceedings will be brought. Not doubt counter-arguments will be made that the bridge was badly maintained, or inadequately protected and that contributed to the collapse. Another lawyer’s feeding frenzy.

So, could this casualty have been deliberate? Not a chance in my view. Negligence might have been involved, but there is no evidence of anything sinister. A plot to deliberately ram a bridge would necessarily involve the ship’s captain and other crew members, or a Pilot – who would all know of the intensity of the resulting investigation and be aware of the severe consequences for them if found guilty of terrorism.

They would know that the ship would soon be crawling with the USCG, surveyors, casualty investigators and a very plague of lawyers, making it unlikely that a plot to destroy the bridge could be kept hidden. The USCG has been known to offer a financial reward or a green card to whistleblowers. And why do a terrorist act and then keep quiet about it and pretend it was an accident?

The arguments I have seen ‘proving’ that the collision was deliberate are nonsense. ‘How could the crew make a distress call when the ship had no electric power?’ Answer, the radio has its own back-up battery. Chinese hackers took control of the ship and caused her to ram the bridge supports? Impossible. Navigational equipment is not connected to the internet and steering in and out of port is by hand.

No, this was an accident, a fortuity. But what do you think? Conspiracy or a wild theory? Vote below.

Optional further reading: The joke letter below, from a Captain to his head office, circulated around the British Merchant Navy when I was at sea. It has some relevance and shows that when things go wrong on a ship, they can go very wrong indeed.

Dear Sirs:

It is with regret and haste that I write this letter. Regret that such a small misunderstanding could lead to the following circumstances, and haste so that you will get this before you form your own preconceived opinions from reports in the world press. For I am sure that they will overdramatise the affair.

We had just picked up the pilot and the deck apprentice had returned from changing the ‘G’ flag for the ‘H’ flag. This being his first trip he was having difficulty rolling up the ‘G’ flag. I therefore showed him how it should be done. Coming to the last part I told him to "let go". The lad, willing but not too bright, I had to repeat the order in a sharper tone of voice.

At this moment, the Chief Officer appeared from the chartroom where he had been plotting the ships passage and thinking that it was the anchor that was being referred to, repeated the " let go " order to the Third Mate on the foc'sle. The port anchor, having been cleared away but not walked out, was promptly let go. The effect of letting the anchor drop while the vessel was moving at full harbour speed proved too much for the windlass brake, and the entire length of the port cable was pulled out by the roots. I fear that the damage to the chain locker may be extensive. The braking effect of the anchor naturally caused the vessel to sheer in that direction and towards a swing-bridge that spans a tributary to the river up which we were proceeding.

The swing-bridge operator showed great presence of mind by opening the span for my vessel to go through. Unfortunately, he had not thought of stopping the traffic, resulting in a Volkswagen, two cyclists and a cattle truck being deposited on the foredeck. My ship’s company are at present rounding-up the contents of the latter, which from the noise, I would say are pigs. In his effort to stop the progress of the vessel, the Third Mate dropped the starboard anchor, sadly too late to be of use, and it fell on top of the swing-bridge operators control cabin.

After the port anchor was let go and the vessel started to sheer, I rang ‘full astern’ on the engineroom telegraph, and personally telephoned the engineroom to order maximum revolutions. I was informed that the sea temperature was 53 degrees and was asked if there was going to be a film tonight. My reply would not contribute constructively to this report.

Up to now I have confined my report to the activities at the forward end of my vessel. Back aft they were having their own problems. As the port anchor was let-go the Second Mate was supervising the making-fast of the aft tug and was lowering the ship’s towing spring onto it. The sudden braking effect of the port anchor caused the tug to run in under the stern of my vessel just as the propellor answered my double ring for ‘Full Astern.’ The Second Mate’s prompt action in securing the inboard end of the towing spring delayed the sinking of the tug by several minutes thereby allowing the abandonment of the tug.

It is strange, but at that very moment of letting go the port anchor, there was a power cut ashore. The fact that we were passing over a ‘cable area’ at the time might suggest that we may have touched something on the bottom of the riverbed. It is fortunate that the high-tension cables brought down by the foremast were not live, possibly they had been replaced by the underwater cable. But owing to the shore blackout, it is impossible to say where the pylon fell.

It never fails to amaze me, the action and behaviour of foreigners during moments of crisis. The Pilot for instance, is now huddled in the corner of my day-cabin, alternately crooning to himself and crying, after having consumed a bottle of my gin in a time that is worthy of inclusion in the Guinness Book of Records. The tug captain, on the other hand, acted violently and had to be forcibly restrained by the Steward, who now has him handcuffed in the ship's hospital where he keeps telling me to do impossible things with my ship and my person.

I enclose the names and addresses of the drivers and the insurance companies of the vehicles on my foredeck which the Third Officer collected after his hurried evacuation of the foc'sle. These particulars will enable you to claim for the damage that they caused to the railings at number one hold.

I am enclosing this preliminary report, for I am finding it difficult to concentrate with the sound of the police sirens and their flashing lights. It is sad to think that had the Apprentice realised that there was no need to fly pilot flags after dark none of this would have happened. For the weekly Accountability Report I will assign the following casualty numbers: T75001 to T75100, incl.,

Yours very truly, .............. Master