As the dust settles on the ‘landslide’ created by Labour’s 1.72% increase in the share of the vote, and the Liberal Democrats beam at the addition of 63 seats by their share increasing by 0.64%, there are inevitable calls for reform of the voting system, not least from Reform UK and The Green Party who are the latest to suffer from the ‘First Past The Post’ system. This justifiable clamour will, however, mask the equally important review of the Upper Chamber, the House of Lords.

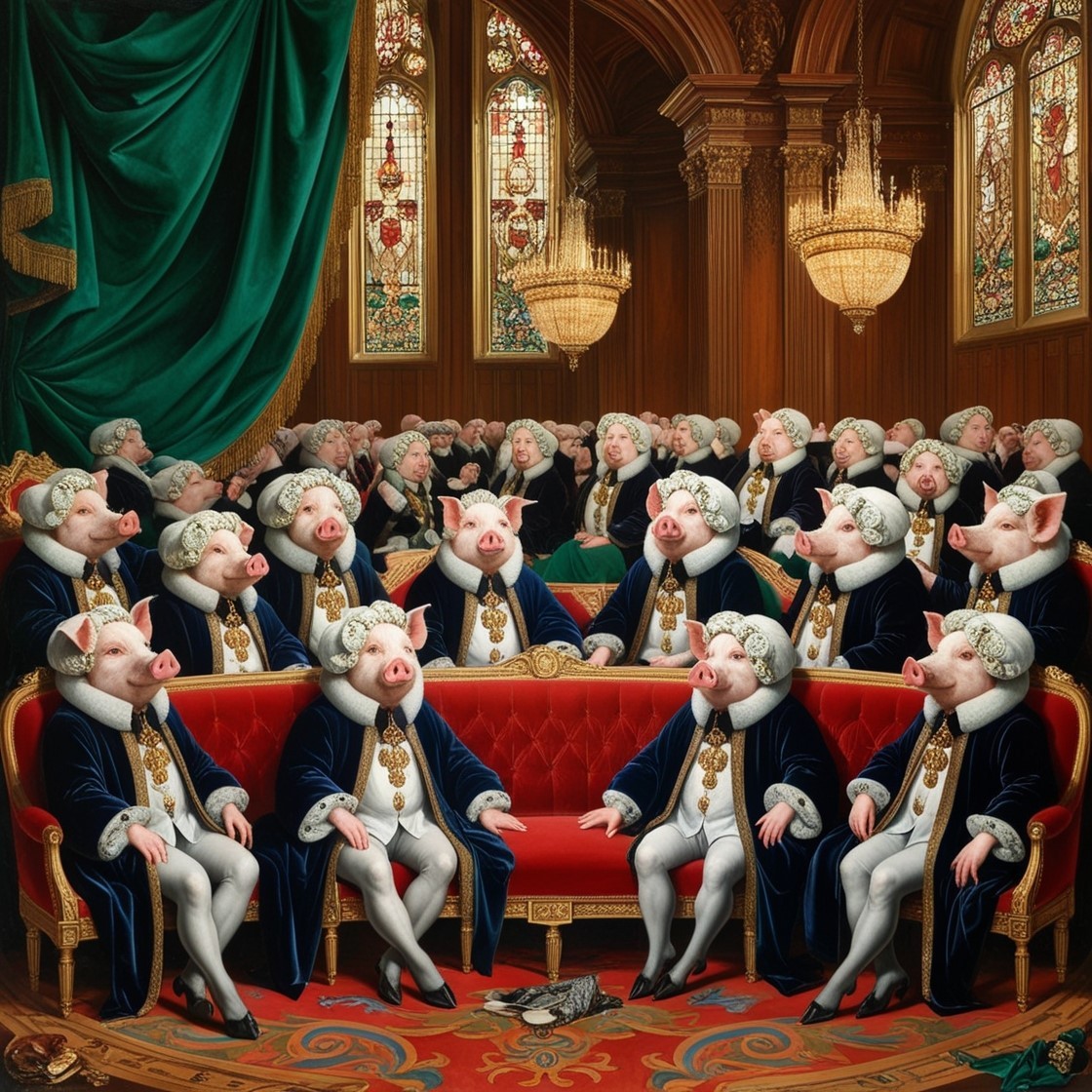

The House of Lords is commonly viewed as an anachronistic, constitutional heirloom that had remained largely unchanged until the reform enacted by Tony Blair made it even worse. The reality is that the Lords has experienced continual change since its early development in the 11th century from the Great Council. It reigned supreme over the House of Commons, had something of a rocky experience when Cromwell reduced its powers before it was abolished by an Act of Parliament in 1649, which declared that "The Commons of England find by too long experience that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England."

With the restoration of the Monarchy came the return of the Lords, and as the most powerful chamber until the 19th century. Over the course of the century, the powers of the upper house were further reduced, culminating in the Parliament Act of 1911 that effectively made the Commons the stronger House.

In the last 30 years there has been constant reviews and proposals, across the political spectrum, though with little enactment. The current chamber has 785 peers, making it the second largest parliamentary chamber in the world. Only China's National People's Congress is bigger.

So what does Starmer plan to do? Previously, he said he would abolish the “undemocratic and indefensible” chamber altogether and replace it with a fully elected body. Instead, Labour's manifesto says the party would consult on replacing the Lords with a "more representative" alternative. This seems to include phasing out the remaining hereditary peers and members would have to retire at the end of the Parliament following their 80th birthday. The manifesto said that Lords reform is “long overdue and essential” so a clear commitment to reform, assuming they do intend to deliver on their manifesto commitments.

There always appears to be consensus on the need for reform, but the real argument is about what form the revised chamber should take. The function of the Lords is now well established, best encapsulated as a ‘revising chamber’. A place where more time is available to scrutinise proposed legislation and ‘suggest’ amendments. This aligns with the backdrop of the Commons short termism, driven by limited time in political office, to a longer term view in the Lords (previously provided by the hereditary peers representing the long established families in England).

Proposals over the last few decades range from complete abolition to either a completely directly elected second chamber (similar to the 100 member US Senate) or a fully appointed model (similar to the 105 member Canadian Senate). The most popular models appear to be a hybrid of these extremes with ‘expertise’ provided by appointees and the democratic element provided by elected members.

The importance placed on Lords reform by Starmer’s government will soon be evident.

Richard Scott