I was a hong xiao bing, a junior Red Guard, one of the army of children Mao Zedong used to further his demented ideology. I was too young to be a real Red Guard, but I saw some terrible things, things that haunt me still. And as I look around today’s Britain, Europe and the US, I see similarities with Mao’s insane cultural revolution all around, getting worse and worse, so I would like to tell you this cautionary tale of tyranny and totalitarianism.

My name is not Zhang Yingyue, but that is the name I shall use, for I still have family in China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would not hesitate to punish them for me saying things they do not like.

I was born in 1958, in Beijing China into a family of some status, my mother and father both having joined the CCP before it came to power, to fight against the Japanese invader. We were poor, but a little richer than most people, and we lived near Tiananmen Square in Central Beijing.

One of my first memories is being hungry, at the end of Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward that killed up to 45 million, mainly by starvation. I remember that we had to give the Party our metal cooking pots and pans to make steel in backstreet furnaces that produced steel of such poor quality that it could not be used, making it difficult to cook what little food was available. Even small children like me were used to kill birds, so that they would not eat grain and other crops. This led to too many insects, which ate more crops than the birds. I now see a mirror image of all this insanity in the West’s Great Leap Backwards, also known as Net Zero.

Starting elementary school at age seven, the first thing we did was to join the hong xiao bing, the junior Red Guards. This was at the beginning of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which had the aim of destroying all traces of the old China. The first thing we did on arriving at school each day was to bow before a giant picture of Mao in the yard and swear to obey his thought and be good revolutionaries. We had to study his Little Red Book for an hour daily, learning it by heart. One of our first lessons was about destroying the Four Olds; old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. Even our school had to change its name, to Red Flag school. Again, I see echoes of this here in Britain, where the ruling class is obviously trying to destroy the old British values and slandering British history and society. These cultural vandals are copying the ideas and methods of the most murderous person in history, worse even than his fellow socialists, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler and Pol Pot.

The Cultural Revolution was surely the craziest time in history, with brainwashed teenage fanatics given free reign. They tore down and destroyed priceless monuments and artifacts, and made false accusations against innocent people, beat them up and killed many. Massacres happened all over China. Another million and a half people died. Many more had their lives destroyed, millions ending up in re-education camps, my own father and mother among them.

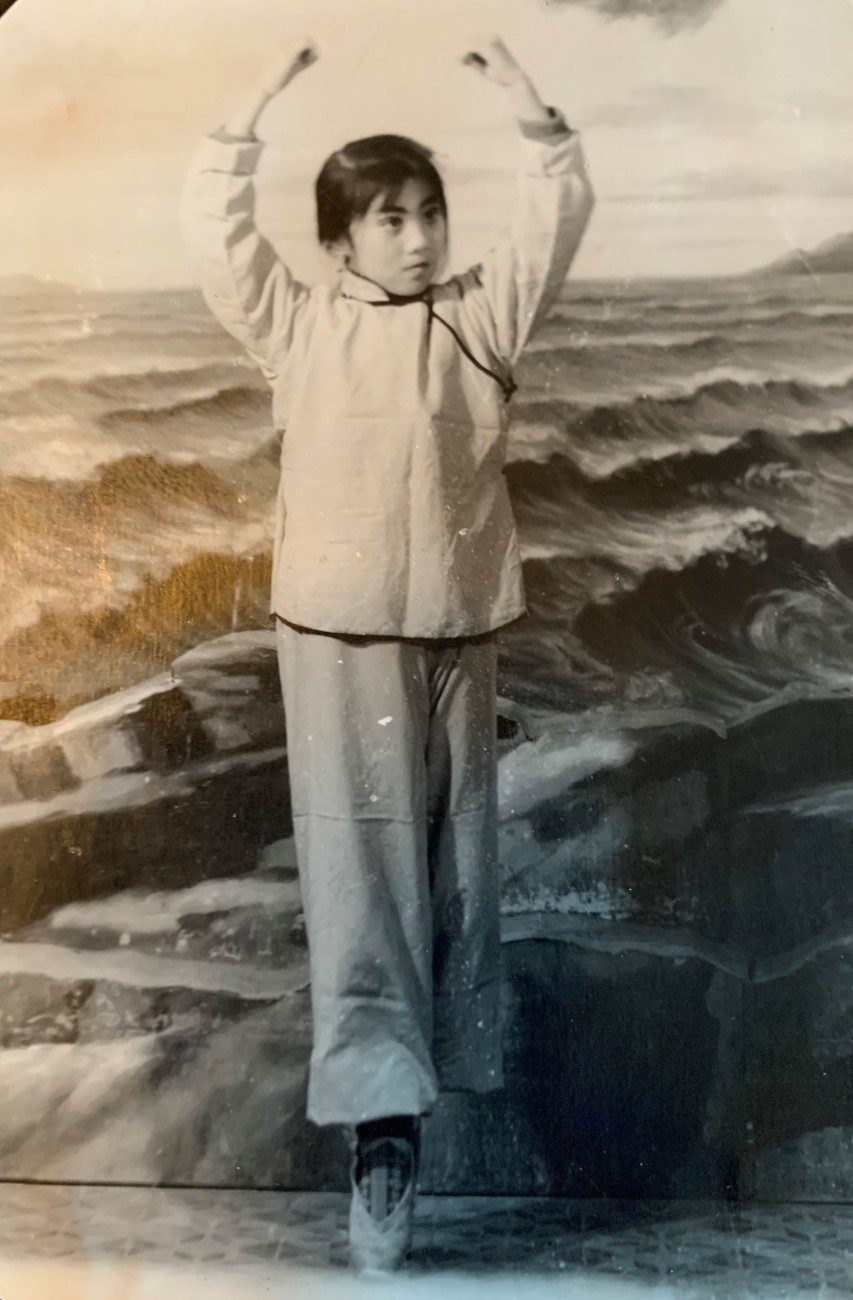

Mum was in the camp for five years, Dad for eleven. Because my parents were regarded as enemies of the Party, I was singled out for abuse at school, by the teachers as well as other children, and the slightest mistake resulted in beatings and other punishment. I was a little lucky as I was chosen to go to ballet school. That was even more brutal, but at least the brutality was shared around evenly.

Things were hard at home too. I lived with my grandmother, who was very old. Her feet had been bound when she was young, and she could not walk very far. I had to do all the shopping, go see a doctor by myself and grow up very fast. I was frightened all the time. Frightened about saying something that was the wrong thing and being accused of counter-revolutionary thought. I remember being forced, aged about ten, to go on a march. We all had to follow a chant by an older boy, who shouted ‘long live Chairman Mao, down with the four olds’ or something similar. After a few hours of this, he made a mistake and shouted the reverse, ‘down with Chairman Mao’. He was taken away and not seen again. He would have been about 15.

I was frightened that I would not see my mother and father again, frightened they would take my grandmother away, frightened of being beaten, and frightened of being incinerated in a nuclear war. We were told that the Soviet Union had been taken over by counter-revolutionaries and was planning to drop a nuclear bomb on us, which reminds me of the brainwashing we are getting about the war in Ukraine. We were forced to help dig tunnels under Beijing for bomb shelters.

And I was very lucky that I was not a few years older. They sent hundreds of thousands of teenagers from big cities like Beijing out into the primitive, backward countryside, to ‘learn from the peasants’. What most of them learned was that the peasants didn’t want them and thought that they were soft, over-privileged city kids, to be worked half to death and treated as badly as they saw fit. Many, very many, of the girls were raped. Some never came back.

I even frightened myself. I remember lying in bed at night, under the blankets, building up my courage to whisper ‘down with Chairman Mao’ out loud, half expecting the gonganbu, the Party’s security police, to break down my bedroom door and drag me away to some terrible fate. I was frightened by many of the things I saw, such as adult neighbours being dragged down the street while being kicked and punched by teenage Red Guard neighbours, who were screaming abuse at them. The sight of hate-filled BLM, Antifa and pro-Palestine demonstrations brings it all back. Sometimes we children were encouraged to throw things at the people being denounced. I still feel shame about what I did.

I recall, before they were sent to the (separate) camps, my father destroying my mother’s beautiful old-style dresses in case they were found, and she was accused of being a supporter of the Four Olds. She had already destroyed all her old photographs and changed her place and date of birth, to hide the fact of her being educated in a French convent school, an automatic flag as a probable capitalist-roader, no matter that she was a CCP member and had fought against the Japanese. That was no protection, just the opposite, and they were both denounced and sent to camps. I still don’t know what they were accused of, or who denounced them, as they refused to talk about it when it was all over and they came home.

The insanity pervaded all of society, and almost every social interaction. On going into a store to buy something, the conversation went something like ‘Long live Chairman Mao! Have you any pork?’ The shop worker would reply ‘Long live Chairman Mao. No.’ and then one would say ‘‘Long live Chairman Mao. What do you have? And the reply might be something like ‘‘Long live Chairman Mao, we have some chicken’s feet, do you want them? And the reply, as you will have guessed, would be ‘‘Long live Chairman Mao, yes please.’ Sadly, I’m not joking. The consequences of failing to follow this line of speech could be very serious, laughable though that might sound. But is it so very different to the consequences some people have suffered here by failing to follow the approved line of speech on men becoming women, or race or Islam?

I had to grow up being very careful of what I said, and not really trusting anyone, as there was no defence against even obviously false, malicious accusations of opposing the Party. An accusation was enough for you to be guilty. I learned to look for hidden meanings in what people said, and to pretend to believe in what was obvious nonsense with all my heart. But I did believe in a lot of it. I believed, because we were told every day, that people in the West, Britain, Europe and the USA were starving and cruelly oppressed, much like people now believe what they are told about Russia. I believed that China was the richest country in the world. The Party had made it so, and we had more natural resources than the rest of the world combined, and that the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America needed China to come and liberate them. All lies of course. Now, here in Britain, we are told the opposite lies, like Britain being the worst at everything, constantly falling behind the EU countries and that we have no resources or, where we do, we can’t touch them because of Net Zero.

And then Mao died. The hysteria was overwhelming. We cried in the street (it was dangerous not to), and we pulled our hair and cried out ‘who will look after us now?’ The extreme Gang of Four, led by Mao’s last wife, Jiang Qing, took over, but the chaos they caused was too much even for the CCP, and they were deposed. Deng Xiaoping fought his way to the top. At first, nobody was sure about him, as he had also suffered during the Cultural Revolution and had been denounced.

But then spring was in the air and the first, fragile shoots of relative freedom were seen. Nixon’s visit to China a few years earlier had let in a crack of light. That was followed a year later by a visit from the Philadelphia Orchestra, which I remember well, and attended a concert myself. We were stunned by the Americans, how good they were musically, and how well-dressed, open and friendly they were, completely opposite to the downtrodden starving poor we had been told about. I still get emotional thinking about it.

And things got even better. About 1979, flared trousers become all the rage with we youngsters, and Boney M’s Rivers of Babylon became wildly popular, as did disco dancing in parks. We had seen nothing like it before, having worn only drab-coloured Mao suites, and listened to revolutionary music and dancing revolutionary dances. Here was a cultural revolution we could all get behind.

But it was not to last, as the murders in Tiananmen Square, and the repression under Xi Jinping have shown. Any freedom the Chinese people were given was just as easily taken away. It all depends on the mood of our CCP dictators. I am a British citizen now, and my children are British. But I worry about their future. The thought of them going through what I did, and the possible loss of their freedom fills me with terror. The talk of war and conscription fills me with dread. I love Britain and I do not want to see it end up a dictatorship. But the signs are not good.

The terror of the Cultural revolution was the result of a small but over-powerful group of ideologues, in charge of a virile but virulent dogma, the sole depository of the truth, or the truth they want to force on society, who used, misused and abused the natural enthusiasm and idealism of youth for their own perverted ends, very similar to those in the West busy creating their New World Order through their very own Cultural Revolution.

Do not take your freedom for granted.

Zhang Yingyue