Haven’t we come a long way since ARPANET, the Internet’s venerated ancestor. The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network to give it its full monicker was developed in the late 1960s. Its initial purpose was to link computers at Pentagon-funded research institutions over telephone lines. It was no ad hoc shoestring enterprise, either. Driven mostly by military needs to have a computerised control system with a central core to it, even in the 60s the system required six years and $61 billion to implement.

Now for those stricken with eyes heavy of lid, liable to crash shut at the mere mention of a computer, quicker even maybe than the blinds on every red-light district window just after the world’s great and the good blow into town on one of their perennial international junkets, let me reassure you. Stay with me on this, since I'm not really writing about machines or computing.

A deep study of the title to this article should clue you in. The fact is that personalities and attitudes matter. Briefly then, it was a chap called Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider, or just plain “lick” to his mates, who would become the first director of ARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO). His tenure signalled the beginnings of its demilitarisation. His 1960 essay i, concerning “man-computer symbiosis” is still considered one of the most important in the history of computing, Licklider posited the then-radical belief that a marriage of the human mind with the computer would eventually result in better decision-making.

Credited with creating the Internet two years after ARPANET was effectively abandoned and later formally decommissioned, Tim Berners-Lee ran a programme called Enquire that he created for his own personal use while employed at CERN, which could store information in files that contained connections (or “links”) both within and among separate files, now known as hypertext. Network Control Protocol had given way to TCP/IP and the rest is history. Yay for the Brits!

Threaded right through all of this though, is a common theme. As Licklider had correctly understood, it was the technical communication as human investment aspect of it all that counted much more than the machinery itself. Among the world’s power brokers and society in general there quickly arose a somewhat utopian conviction that humans and computers could together create a better world. People started writing stuff with titles in them such as, “The Internet: An Unprecedented and Unparalleled Platform for Innovation and Change.” Well, I’ve heard some

management-speak in my time but that one is actually straight out of the annals of the World Intellectual Property Organization in 2012.

And why not? Among many there’s no less a sense of unbridled hope and optimism whenever a brand-new solar panel array or wind farm pops up in the landscape. Same with the Internet I’d argue. Who hasn’t heard that The Information Super-Highway is: this company’s route to prosperity; this or that society’s solution to a parlous deficit in learning; my community and source of refuge in a world of turmoil and hate; the means to set humanity free and unleash the bright forces of democracy all over the world by breaking down the walls of authoritarian regimes everywhere; or merely the means to stop misinformation in its tracks by promoting reasoned debate for everyone?

Well, I know I have. I’ve heard much of that over the years, and it’s been going on ever since the birth of the Internet. Statements by WIPO like the example earlier do strike me as being a little glib, as do many of those I’ve just outlined.

Let’s never forget on the other hand that the map defining ARPANET’s hardware, for all its optimistic adherents in the early days describes geographically a military landscape situated in the USA. Where are the first windmills today? Where are the solar arrays? Why are they found where they are? Such apparatus does not arise from the mists of optimism. It arises from hard desire to achieve specific purposes.

But the Internet is just the tool; it’s people who do the talking, I hear you cry. Using the tool for your own ends is not new, I grant. Ben Johnson is famous for it, going right back to the year 1620 when he wrote the masque, News from the New World Discovered in the Moon, in which he sells everyone the idea that life describable in much detail had been found on the moon. Journalism was just getting started in Jacobean times and Johnson was sceptical of it. His aim was mischief, intended to satirise the news-hungry for their outright gullibility.

While acknowledging that analogy is not precedent, one must nevertheless wonder what is new about the spread of misinformation. In fact, using analogy as precedent is tantamount some might say to creating a pretext and that no one is immune. Many are familiar with the Harry Enfield character who was always apologising for the, “actions of my government during ze vorrr.” What was so funny is that that’s exactly what the German government was often doing. German policy often mentioned avoidance of its Nazi and Stasi past in order to justify its actions. The Soviets as we all know engaged in much deliberately directed disinformation, so much so that the Finns invested heavily in literacy in order to counter it.

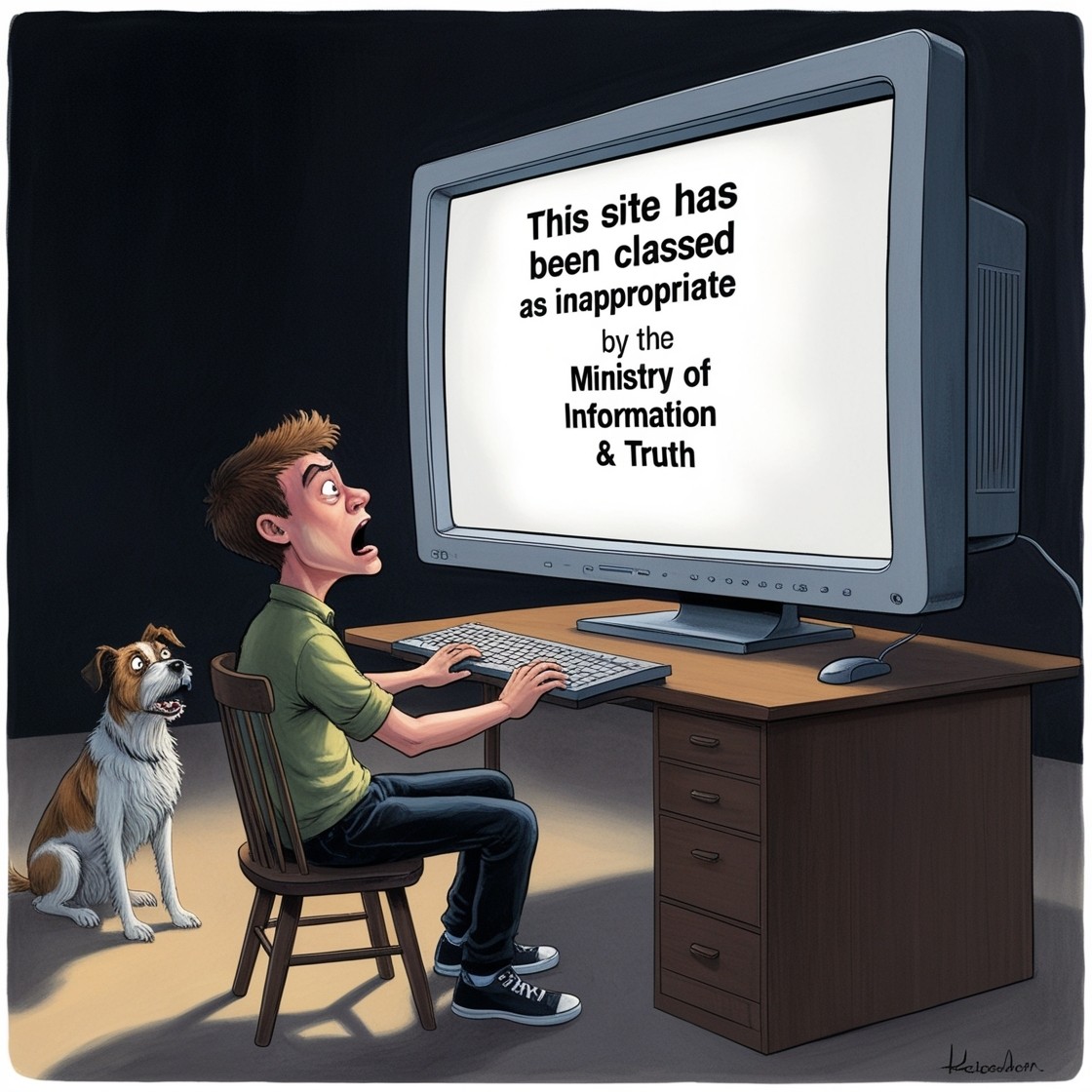

Our own governments successively are careful to point up the benefits of the Internet while carefully suggesting that benefits can only accrue if proper control is exercised from above. Increasingly this sounds like so much lip service to me. Liberty it appears can only be allowed in terms that John Locke promoted, “Where there is no law there is no freedom”.

If anyone thinks that this is a peculiarly conservative aspiration, then they need to think again. The current government might not actually be a conservative one, but it is in perfect lockstep with the likes of Matt Hancock ii who argued in 2017 that “what we need to do to harness [the Internet’s] exponential power, while preventing harm and abuse, so that it serves humanity, spreads human ingenuity and enhances human freedom” and “Our task is to strike the right balance between freedoms and responsibilities online, such that the solutions can be applied globally, and the whole free world can emulate our approach” and “Just this morning on the Today programme you may have heard Evan Williams, co-founder of Twitter make the same point, “You can be an ardent believer in free speech and also realise that someone’s speech can limit someone else’s willingness to speak.””

Well, glad I got that straight then. There’s no new “crackdown” coming. It’s all just a continuation of antecedent precedent. At this point I’m tempted to make up an analogy of my own using that old philosophical saw concerning the potential sound of a tree falling in a forest where there’s no one in its vicinity to actually hear it coming down. Would I be made into an idiot just because the Idiots’ Lantern in the corner of my living room were left chugging away while I’m out back pottering in my garage?

Idiots like looking at lanterns in the same way that the gullible love to drink in the news to satisfy their own predilections. For the Libertarian the future looks bleak. Someone else with the power will be deciding what Liberty looks like from now on. The years between 1960 and 2012 of unrelenting optimism concerning the Internet have run their course and by 2017 we hear not a litany by those proclaiming its limitless power for good, but one from precisely the same quarters proclaiming its limitless power for harm.